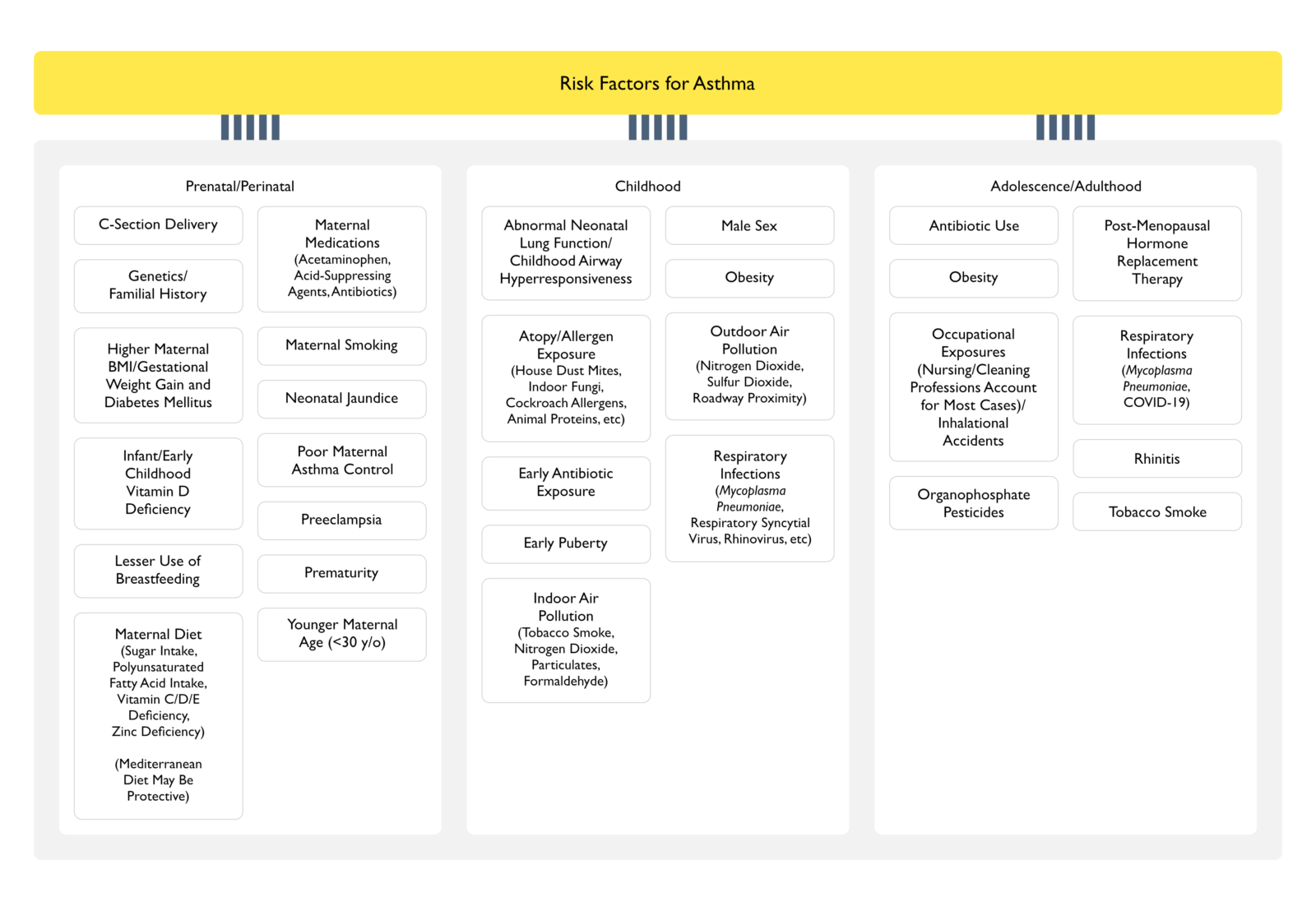

Risk Factors for Asthma

Prenatal/Perinatal

- C-Section Delivery

- Genetics/Familial History

- Higher Maternal Body Mass Index (BMI)/Gestational Weight Gain and Diabetes Mellitus (see Obesity Diabetes Mellitus)

- Infant/Early Childhood Vitamin D Deficiency (xxxx)

- Lesser Use of Breastfeeing

- Maternal Diet

- Maternal Medications

- Neonatal Jaundice

- Poor Maternal Asthma Control

- Preeclampsia (see xxxx)

- Prematurity

- Younger Maternal Age (<30 y/o)

Childhood

- Abnormal Neonatal Lung Function/Childhood Airway Hyperresponsiveness

- Atopy/Allergen Exposure

- Epidemiology

- The Association Between Asthma and Other Atopic Diseases (Such as Allergic Rhinitis) is Well-Established

- However, Sensitized Patients Do Not Necessarily Develop Allergic Disease

- Research Suggests that the Early Life Microbiome Likely Influences the Likelihood that an Allergic Predisposition Results in Asthma

- The Association Between Asthma and Other Atopic Diseases (Such as Allergic Rhinitis) is Well-Established

- Diagnosis

- Serum IgE Levels are Closely Linked with Airway Hyperresponsiveness, Whether or Not Asthma Symptoms are Present (NEJM, 1989) [MEDLINE] (NEJM, 1991) [MEDLINE] (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2007) [MEDLINE] (J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2007) [MEDLINE]

- Elevations Serum IgE Levels Indicate the Presence of Allergic Sensitization, Although This Level Provides No Information About the Specific Allergens to Which a Patient is Sensitized

- Serum IgE Levels are Closely Linked with Airway Hyperresponsiveness, Whether or Not Asthma Symptoms are Present (NEJM, 1989) [MEDLINE] (NEJM, 1991) [MEDLINE] (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2007) [MEDLINE] (J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2007) [MEDLINE]

- Etiologies of Allergen Exposure

- Animal Proteins (Predominantly Cat and Dog)

- Although Unclear Why, Early Life Exposure to Farm Animals is Negatively Associated with the dDevelopment of Allergic Disease

- Cockroach Allergens

- Predominantly in Studies Conducted in Urban Settings

- House Dust Mites

- Indoor Fungi (Penicillium, Aspergillus, and Cladosporium)

- Animal Proteins (Predominantly Cat and Dog)

- Epidemiology

- Early Antibiotic Exposure

- Epidemiology

- Documented in Retrospective Studies, But the Association Did Not Reach Statistical Significance in Prospective Studies

- Epidemiology

- Early Puberty

- Indoor Air Pollution

- Formaldehyde (see Formaldehyde)

- Nitrogen Dioxide (see Nitrogen Dioxide)

- Particulates

- Tobacco Smoke (see Tobacco)

- Male Sex

- Epidemiology

- Childhood Asthma Tends to Be a Predominantly Male Disease, with the Relative Male Predominance Being Maximal at Puberty (Front Immunol, 2017) [MEDLINE]

- However, After Age 20, the Prevalence is Approximately Equal Between Males and Females Until Age 40, When the Disease Becomes More Common in Females (Mayo Clin Proc, 2021) [MEDLINE]

- Potential Explanations for Male/Female Difference in Asthma Prevalence

- Differences in Symptom Reporting Between Male and Female Children

- Greater Prevalence of Atopy (Evidence of Immunoglobulin E Sensitization to Allergens) in Young Males

- Decreased Relative Airway Size in Males, as Compared to Females (Pediatr Pulmonol, 1995) [MEDLINE]

- Smaller Airway Size May Also Contribute to Increased Risk of Wheezing After Viral Respiratory Infections in Young Males, as Compared to Females

- Epidemiology

- Outdoor Air Pollution

- Nitrogen Dioxide (see Nitrogen Dioxide)

- Roadway Proximity

- Sulfur Dioxide (see Sulfur Dioxide)

- Obesity (see Obesity)

- Epidemiology

- Increased Asthma Prevalence Has Been Reported in Obese Children with a Dose-Dependent Effect of Body Mass Index (BMI) on Asthma Risk (BMC Pediatr, 2013) [MEDLINE]

- Epidemiology

- Respiratory Infections

- Etiology

- Mycoplasma Pneumoniae (see Mycoplasma Pneumoniae): infection in childhood/adulthood is associated with the development of asthma within the first 2 years after infection

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) (see Respiratory Syncytial Virus): infection in infancy is associated with later development of asthma

- Rhinovirus (see Rhinovirus): infection in infancy is associated with later development of asthma

- Etiology

Adolescence/Adulthood

- Obesity (see Obesity)

- Epidemiology

- Age-Adjusted Prevalence Rates for Asthma and Obesity are Increasing in the United States

- Evidence Suggests that Adults with an Elevated Body Mass Index (BMI) are at Increased Risk for Asthma (Arch Intern Med, 1999) [MEDLINE] (BMJ, 2000) [MEDLINE] (Arch Intern Med, 2001) [MEDLINE] (Allergy Clin Immunol, 2005) [MEDLINE] (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2007) [MEDLINE] (J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2009) [MEDLINE] (Eur Respir J, 2009) [MEDLINE] (J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2018) [MEDLINE]

- Risk May Be Greater for Nonallergic Asthma than Allergic Asthma (Chest, 2006) [MEDLINE]

- Epidemiology

- Occupational Exposures

- Epidemiology

- The European Community Respiratory Health Surveys (ECRHS and ECRHS-II) has identified several occupations that are associated with an increased risk of new-onset asthma; nursing and cleaning were responsible for the most cases (Lancet, 2007) [MEDLINE]

- Etiology

- Cleaning Professions

- Nursing Profession

- Inhalational Accidents: fires, mixing cleaning agents, industrial spills were also associated with an increased risk of new-onset asthma

- Epidemiology

- Organophosphate Pesticides (see Organophosphates/Carbamates)

- Epidemiology

- In the Agricultural Health Study of 25,814 adult farm women, growing up on a farm was protective against asthma, but use of certain pesticides (eg, organophosphates) was associated with an increased risk of adult-onset atopic asthma (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2008) [MEDLINE]

- Epidemiology

- Postmenopausal Hormone Replacement Therapy (see xxxx)

- Epidemiology

- Modest Increase in Risk of Asthma

- Some studies have reported an increased risk associated with combination estrogen-progesterone therapy and others only with unopposed estrogen

- In one study, prior histories of allergy or never-smoking appeared to enhance the risk

- Epidemiology

- Rhinitis (see Allergic Rhinitis)

- Epidemiology

- Adults with Rhinitis are at Greater Risk than those without Rhinitis for Developing Adult-Onset Asthma (Chest, 1999) [MEDLINE] (J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2002) [MEDLINE] (J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2007) [MEDLINE]

- Prospective Multicenter Study of Relationship Between Rhinitis and Asthma (Lancet, 2008) [MEDLINE]: n = 6461 adults (age 20-44 y/o)

- Participants were randomly chosen from the general population, and a cohort without asthma was evaluated with questionnaires, allergen skin testing, serum specific and total immunoglobulin E (IgE), pulmonary function testing, and bronchial responsiveness testing. Subjects were divided into four groups and followed for a mean period of 8.8 years

- The probability of developing asthma during the observation period was:

- For those without evidence of atopy or rhinitis – 1.1%

- Atopy but no rhinitis – 1.9%

- No atopy but with rhinitis (ie, nonallergic rhinitis) – 3.1%

- With allergic rhinitis – 4%

- The adjusted risk ratio for those with allergic rhinitis was 3.5 (95% CI 2.1-5.9) and for non-allergic rhinitis, 2.1 (CI 1.6-4.5), after controlling for country of origin, sex, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), total IgE, family history of asthma, baseline age, BMI, respiratory infections in childhood, and smoking.

- Epidemiology

- Tobacco Smoke (see Tobacco)

- Epidemiology

- Population-Based Studies Demonstrate a Relationship Between Smoking and Airway Hyperresponsiveness

- Studies Also Provided Demonstrate Evidence for an Association Between Primary/Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Asthma Development

- Epidemiology

Agents that Provoke Airway Narrowing

- Aeroallergens

- IgE-mediated, cysteinyl leukotriene-mediated, may cause late asthmatic responses): animal (hair/ scales/ urine/ serum/ arthropod remains), vegetable (wood/ roots/leaves/flowers/cereal/grains/rye grass pollen/ soya beans/ green coffee and castor beans/ arabic, adragante, karaya gums), textiles (cotton/ jute/ flax/ hemp), chemical allergens (PCN/ ampicillin/ cephalosporin powder/ macrolides/ tetracyclines), metals (chromium/ nickel/ platinum/ vanadium/ mercury/ cobalt), plastics (isocyanates/ pthalic and trimellitic anhydrides/ formaldehyde/ latex)

- Exercise: induces airway narrowing in 70-80% of childhood, adult asthmatics (due to changes in lining fluid osmolarity due to drying, rewarming with vasodilation/ cysteinyl leukotriene-mediated) -Exercise does not cause asthma, but is an indirect stimulus (mediated by cysteinyl leukotrienes) for bronchoconstriction in asthmatics -Exercise typically causes early bronchodilation in asthmatics (for 1-3 min) -> exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (peaks at 10-15 min) -> resolution within 60 min

- Osmotic stimuli: hyperventilation with cold or dry air/inhalation of nonisotonic aerosols cause prompt airway narrowing in asthma (probably due to changes in osmolarity of lining fluid/ cysteinyl leukotriene-mediated) and also in COPD (to a lesser extent) -Blocked by cholinergic antagonists, inhibited by cromones (suggests neural mechanism) -Poorly controlled case reports of late asthmatic response after exercise (possibly due to release of different mediators, etc.)

- Infection (probably neurally-mediated): viral respiratory infections are believed to be most common cause of exacerbation in asthma (although evidence is scanty)/ extracts of H. Flu cause induce early and late asthmatic responses (may cause exacerbations in adults but probably not children)

- Sulfur Dioxide (see Sulfur Dioxide, [[Sulfur Dioxide]]): concentrations as low as 1 ppm (even after only 3 min exposures) cause severe bronchoconstriction in asthmatics (>5 ppm usually required in normals)/ patients with persistent asthma respond in a dose-dependent manner/exercise potentiates sulfur dioxide-induced bronchoconstriction (increases delivery to lower airways)/ dry air potentiates the effect of sulfur dioxide/ some wines and beers contain metabisulfite (which produces sulfur dioxide)/ probably acts via sensory nerve endings (cromones protect against it)

- Air Pollution (contains sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ozone, particulates): ozone in air pollution is an acute bronchoconstrictor/ exposure to pollutants can increase allergic responses/low level chronic nitrogen dioxide can increase airway reactivity/ particulate pollution may cause acute asthmatic attacks/ inhalation of sulfuric acid aerosols decreases particle clearance from normal airways

- Odors: strong smells can induce bronchoconstriction

- Weather: increased symptoms during high humidity (increased osmotic or allergen load)/ thunderstorms during high pollen counts cause particle disruption and can induce attacks

- Emotion: stress and hypnotic suggestion induce bronchoconstriction in asthmatics (but usually do not produce attacks)/ hyperventilation (associated with panic attacks) can induce attacks (as described above)

- Reflex Bronchoconstriction: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may induce attacks (especially in children)/ nasobronchial reflex may induce bronchoconstriction in some patients with initial rhinitis/ menstrual, premenstrual exacerbation can occur

- Foods: allergic reactions to nuts may induce asthma/ attacks due to food preservatives (benzoates or tartrazine in ASA-sensitive asthmatics), MSG, coloring agents can be induced in some asthmatic patients with ASA sensitivity

- Drugs

- Propanolol (see Propanolol, [[Propanolol]]): neural mechanism involving blockade of ß2-receptor, not cysteinyl leukotriene-mediated

- Isoproterenol (see Isoproterenol, [[Isoproterenol]])

- Aspirin (ASA) (see xxxx, [[xxxx]]): acetylated >> non-acetylated salicylates/cysteinyl leukotriene-mediated) and NSAID’s

- Crack Cocaine (see Cocaine, [[Cocaine]])

- Radiographic Contrast (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Dipyridamole (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Hydrocortisone (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Interleukin-2 (IL-2) (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Nebulized Pentamidine (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Beclomethasone (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Propellants

- Nitrofurantoin (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Propafenone (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Protamine (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Vinblastine with Mitomycin (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Amiodarone (see xxxx, [[xxxx]])

- Hyperthyroidism (see xxxx, [[xxxx]]): most studies suggest that mild thyrotoxicosis is unlikely to make asthma difficult to control

Etiologic Classification

1) Persistent Asthma: continuing symptoms + chronic airway abnormality (abnormal dose response to histamine/methacholine or increased variation of daily PEFR) -Generally incurable (some cases remit during adolescence) 2) Obstructed Asthma: symptoms + airflow limitation that persist after maximal treatment with bronchodilators and PO steroids/pathologic changes unknown 3) Episodic Asthma: periodic episodes of symptoms (usually requiring treatment) + no detectable abnormality of airway function between episodes -Common type during the pollen season/ sometimes seen early in occupational asthma/ described in non-allergic patients/ pathologic changes are unknown 4) Asthma in Remission: past history of asthma without symptoms or therapy for >12 months (usually have some residual airway hyper reactivity) 5) Potential asthma: typically moderate airway hyperreactivity without symptoms or history of asthma -Particularly occurs in atopic patients 6) Trivial Wheeze: mild or transient wheezing that do not require treatment + normal airway function (absence of airway hyper reactivity) 7) Extrinsic (Atopic) Asthma: asthma in atopic patient (may have attacks in response to non-allergen provoking agents)/ usually positive family history of atopy or asthma/evidence if IgE-mediated mechanisms 8) Occupational Asthma: episodic or persistent asthma due to workplace sensitizer (symptoms and airway narrowing are demonstrated by specific provocation with substance) 9) Intrinsic Asthma: asthma in non-atopic patient (often adult onset)/ usually negative family history of atopy or asthma/ usually no evidence of IgE-mediated mechanisms -May follow severe respiratory illness/ may be refractory

Physiology

- CD4 Lymphocytes: Th2 cells have a predominant role in asthma pathogenesis

- Eosinophils: prominent cells in the airways of many patients with asthma

- Most asthma phenotypes are associated with blood, bone marrow, and lung eosinophilia: eosinophil is a central effector cell in asthma that contributes to ongoing airway inflammation

- Inflammatory Cytokines: Th2 cells regulate allergic inflammation via the production of IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, and IL-13

- IL-13: likely plays a role in inducing allergic asthma -IL-13 has a similar structure to IL-4 and shares the functional receptor, IL-4Rα

- Reactive Oxygen Species: asthma is characterized by altered airway redox chemistry and increased oxidative stress in the airways

- Reactive Nitrogen Species: play a role in asthma pathogenesis

- Arginase: increased arginase activity is observed in allergic asthma

- Arachidonic Acid Metabolites: play a major role in asthma

- Cysteinyl Leukotrienes

- Other 5-Lipoxygenase Pathway Metabolites

- Histamine: causes bronchoconstriction (in both early and late allergic response), vasodilation, leakage of fluid and albumin from postcapillary venules (increased permeability of epithelium to proteins and fluid occurs only during attacks), smooth muscle proliferation

- Histamine is increased in the serum of asthmatics

Airway Remodeling

- Airway Remodeling: cardinal feature of chronic asthma

- Degree of Airway Remodeling is a Function of Disease Severity Over Time

- Asthma Treatments May Have Effects on Airway Remodeling

- Leukotriene Modified Agents Can Decrease Airway Smooth Muscle Mass and Subepithelial Collagen in Animal Models

- Bronchial Thermoplasty Can Decrease Airway Smooth Muscle Mass

- Airway Epithelium: altered in asthma

- Epithelial Basal Lamina: hyalinization and thickening of basal lamina (beneath a normal-appearing epithelial basement membrane) is seen in asthma

- Extracellular Matrix: increased in airway walls in asthma

- Airway Smooth Muscle: increased in asthma

- Goblet Cell Hyperplasia and Mucus Hypersecretion: hallmark of asthma

- Microvascular Changes: bronchial neovascularization is associated with airway remodeling

Physiologic Manifestations

- Airway Hyperresponsiveness

- Diurnal Variation in Airway Responsiveness: normals and asthmatics show increased early morning increases in smooth muscle tone (asthmatics show early morning decreases in PEFR, but normals do not)

- Increased Airway Epithelial Permeability

- Smooth Muscle Hypercontractility

Airflow Limitation

- During Asthma Exacerbation

- Narrowing Occurs in Large Airways, Medium Airways, and Small Bronchi

- Increased Airway Resistance with Decreased Maximal Expiratory Flow

- Airway Narrowing Prevents the Lungs from Completely Emptying Resulting in Gas Trapping: due to resistance to expiratory flow and to bronchial closure at higher than normal lung volumes

- Dynamic Hyperinflation: results in higher total lung volume with increased residual volume (RV)

- Increased Work of Breathing: due to decreased lung/chest wall compliance at higher thoracic volumes and the greater effort required to overcome the resistance of narrowed airways

Pathology

- Pathology (clinical types correlate poorly with pathology):

- Macroscopic (from autopsy cases): hyperinflation/airway plugging with thick secretions (containing eos possibly recruited by IgA, epithelial cells, macrophages, and mast cells/lymphocytes/epithelial cells/ serum)/normal lung parenchyma/thickened airway walls/bronchiectasis (sometimes)

- Microscopic: epithelium infiltration and inflammation (persists between exacerbations and in some cases who are never symptomatic)/desquamated epithelium (due to cationic proteins or elastase from eos/ responds to inhaled steroids after weeks, airway hyperreactivity persists longer)/thickened BM (increased type 3 and 5 collagen, posssibly due to release of the fibroblast mitogen tryptase from mast cells/ may persist even after other features have improved with therapy/ may improve after withdrawal in cases of toluene diisocyanate exposure)/increased cells in lamina propria (especially, eos and mast cells but also lymphocytes, monocytes, basophils, plasma cells)/increased thickness of lamina propria (increased collagen and blood vessels)/increased smooth muscle (hyperplastic and hypertrophic/normal ex vivo contraction properties but abnormal in vivo contraction and relaxation, probably due to esoinophil and lymphocyte products/ possibly due to increased work, histamine, tryptase)/ mucous gland hyperplasia (hyperse-cretion due to chymase and elastase/ adrenergic and cholinergic stimulation)/increased goblet cells/ thickened adventitia (inflammatory cells, few mast cells, increased vessels/ uncouples local parenchymal recoil from smooth muscle)

- Nasal Polyps: smooth, gelatinous, semtranslucent mass of edema tissue with abundant eosinophils, as well as lymphocytes, neutrophils, and mast cells

- Usually arise from ethmoid sinus

- Mechanism: not IgE-mediated (atopy is not more common in nasal polyposis than it is in normals)

Diagnosis

Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) (see Arterial Blood Gas)

- Hypoxemia (see Hypoxemia): due to V/Q mismatch

- Hypocapnia (see Hypocapnia): presence of relative or absolute hypercapnia suggests impending respiratory failure

Bronchoscopy (see Bronchoscopy)

- Friable mucosa

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL): similar to airway washings/findings seen even in mild disease): increased epithelial cells, eos, mast cells or basophils/ prostaglandins, tryptase (in BAL of moder-ately symptomatic asthmatics, suggests ongoing mediator release/in BAL in early allergic res-ponse), chymase (in BAL in early allergic res-ponse), histamine (in BAL between attacks, probably released from basophils), eosinophil products, IgE, albumin (epithelium allows large molecules into lumen)

- Transbronchial Biopsy (TBB): eosinophils present

Chest/Lung Imaging

Chest X-Ray (see Chest X-Ray)

- In the Absence of an Associated Comorbid Disease, Chest X-Ray is Almost Always Normal in Asthma

- Most Clinicians Will Obtain a Chest X-Ray to Evaluate New-Onset, Moderate-Severe Asthma in Adults >40 y/o to Exclude the Alternative Diagnoses Which May Mimic Asthma (Mediastinal Mass with Tracheal Compression, Congestive Heart Failure, etc)

- The Cost-Effectiveness of This Approach Has Not Been Evaluated

- General Indications for Chest X-Ray (and/or Chest CT) Imaging (i.e. Clinical Features Which are Atypical of Asthma)

- Bronchodilator-Unresponsive Moderate-Severe Airflow Obstruction

- Chronic Purulent Sputum Production

- Clubbing (see Clubbing)

- Difficult to Control Asthma

- Fever (see Fever)

- Hemoptysis (see Hemoptysis)

- Inspiratory Crackles

- Need to Evaluate for a Comorbid Disease

- Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) (see Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis)

- Atelectasis Due to Mucus Plugging (see Atelectasis)

- Eosinophilic Pneumonia (see Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia and Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia)

- Persistent Localized Wheezing (see Wheezing)

- May Indicate the Presence of an Airway Foreign Body (see Airway Foreign Body)

- Significant Hypoxemia in the Absence of an Acute Asthma Exacerbation (see Hypoxemia and Respiratory Failure)

- Weight Loss (see Weight Loss)

- Most Clinicians Will Obtain a Chest X-Ray to Evaluate New-Onset, Moderate-Severe Asthma in Adults >40 y/o to Exclude the Alternative Diagnoses Which May Mimic Asthma (Mediastinal Mass with Tracheal Compression, Congestive Heart Failure, etc)

- Recommendations (Global Initiative for Asthma/GINA Guidelines 2016) [MEDLINE]

- Chest X-Ray is Not Routinely Recommended in the Evaluation of Acute Asthma Exacerbation

Chest Computed Tomography (CT)/High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) (see Chest Computed Tomography)

- Specific Indications for Chest CT Imaging (i.e. Conditions in Which CT Imaging Will More Sensitively Detect Abnormal Lung Findings than Would Chest X-Ray)

- Suspicion of Bronchiectasis (see Bronchiectasis)

- Suspicion of Bronchiolitis Obliterans (BO) (see Bronchiolitis Obliterans)

- Suspicion of Emphysema (see Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)

- Suspicion of Tracheobronchomalacia (see Tracheobronchomalacia)

- Suspicion of Vascular Anomalies

- Aberrant Left Subclavian Artery and Right Sided Aortic Arch

Complete Blood Count (CBC) (see Complete Blood Count)

- Mild-Moderate Peripheral Eosinophilia (see Peripheral Eosinophilia): <1,500 Eosinophils/μL (or <15%)

- Peripheral Eosinophilia May Be Absent if the Patient is on Corticosteroids

- While Markedly Increased Eosinophil Levels (>1,500 Eosinophils/μL) Can Be Seen in Allergic Asthma (or in Eosinophilic Asthma without Allergic Sensitization), Alternative Disorders Should Also Be Considered in the Differential Diagnosis

- Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) (see Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis)

- Predisposing Criteria (at Least 1 Must Be Present)

- Asthma

- Cystic Fibrosis (CF) (see Cystic Fibrosis)

- Obligatory Criteria (Both Must Be Present)

- Detectable Aspergillus Fumigatus-Specific IgE (≥0.35 kU/L)

- Aspergillus Skin Test Positivity is Acceptable if Serum Aspergillus-IgE Testing is Unavailable

- Increased Total Serum IgE >500 IU/mL

- IgE <500 IU/mL May Be Acceptable if All of the Other Criteria, Below, are Fulfilled)

- Other Criteria (≥2 Must Be Present)

- High Resolution Chest CT (HRCT) Findings Consistent with Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA)

- Peripheral Eosinophils >500/μL

- Elevated Aspergillus Fumigatus-Specific IgG by Enzyme Immunoassay or Lateral Flow Assay

- Measuring Aspergillus Serum Precipitants is Less Favored Due to Decreased Sensitivity, as Compared to Direct IgG Measurement

- Drug-Induced Pulmonary Eosinophilia (see Drug-Induced Pulmonary Eosinophilia)

- Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) (Churg-Strauss Syndrome) (see Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis)

- Asthma and/or Other Lung Disease (Pulmonary Infiltrates with Eosinophilia, Eosinophilic Pleural Effusion, and/or and Non-Cavitary Pulmonary Nodules)

- Upper Airway/Ear Disease

- Skin/Cardiovascular/Neurologic/Renal/Gastrointestinal/Musculoskeletal Involvement

- Peripheral Lymphadenopathy (see Peripheral Lymphadenopathy)

- Peripheral Eosinophils ≥1,000/μL

- Hypereosinophilic Syndrome (see Hypereosinophilic Syndrome)

- Defined as Peripheral Eosinophils ≥1,500 Eosinophils/μL + Organ Damage and/or Dysfunction Attributable to Tissue Hypereosinophilia (Skin, Lungs, Heart, Vascular, Gastrointestinal, Nervous System) + Exclusion of Other Disorders/Conditions as the Major Reason for Organ Damage

- Strongyloidiasis (see Strongyloidiasis)

- Other Pulmonary Infiltrates with Eosinophilia (PIE) Syndromes (see Pulmonary Infiltrates with Eosinophilia)

- Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) (see Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis)

Electrocardiogram (EKG) (see Electrocardiogram)

- General Comments

- Electrocardiogram (EKG) is Typically Normal in Asthma

- However, Various Abnormalities May Occur During an Asthma Exacerbation

- Sinus Tachycardia (see Sinus Tachycardia)

- Right Axis Deviation (RAD)

- Right Bundle Branch Block (RBBB) (see Right Bundle Branch Block)

- Right Ventricular (RV) Strain

- Ectopy

- However, Various Abnormalities May Occur During an Asthma Exacerbation

- Electrocardiogram (EKG) is Typically Normal in Asthma

Fraction of Exhaled Nitric Oxide (FENO)

Rationale

- While Exhaled Nitric Oxide Measurement May Aid in the Diagnosis of Asthma (in Combination with History and Other Testing), a Normal Exhaled Nitric Oxide Level Does Not Exclude the Diagnosis of Asthma (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2021) [MEDLINE]

- Based on the Observation that Asthma-Associated Eosinophilic (i.e. Type 2) Airway Inflammation Leads to Up-Regulation of Nitric Oxide Synthase in the Respiratory Mucosa, Which Results in Increased Generation of Nitric Oxide Gas in the Exhaled Breath, as Compared to Normal Patients

Interpretation

- Elevated FENO ≥40-50 Parts/Billion Makes the Diagnosis of Asthmatic Airway Inflammation More Likely

- However, Other Potentially Confounding Respiratory Diseases (Such as Allergic Rhinitis, Eosinophilic Bronchitis, etc) Must Be Excluded

- Treatment with Inhaled/Oral Glucocorticoids Decreases Airway Inflammation and Levels of Exhaled Nitric Oxide

Total Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Level (see Serum Immunoglobulin E)

Interpretation

- Increased Total Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Level May Occur in the Absence of Asthma (Including in Allergic Rhinitis, Atopic Dermatitis, etc)

- Very High Total Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Levels (>1,000 IU/mL) are Typically Found in the Following Disorders

- Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) (see Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis)

- Atopic Dermatitis (Especially in Children or in Patients with Very Severe Skin Involvement) (see Atopic Dermatitis)

- Hodgkin Lymphoma (see Hodgkin Lymphoma)

- Hyper IgE Syndrome (Job Syndrome)

- IgE Myeloma (see Multiple Myeloma)

- Parasitic Infections

- Very High Total Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Levels (>1,000 IU/mL) are Typically Found in the Following Disorders

- Allergic Asthma May Be Present in the Absence of an Increased Total Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Level

- Total Serum Immunoglobulin E (IgE) Level May Not Fully Reflect the Levels of Mast Cell-Bound IgE in Airway Tissue

Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) (see Peak Expiratory Flow Rate)

Rationale

- Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) is Used to Monitor Patient with a Known Diagnosis of Asthma or to Assess the Role of a Particular Occupational Exposure/Trigger, Rather than to Make the Primary Diagnosis of Asthma

Technique

- Measurement of Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) During a Brief Forceful Exhalation Can Be Performed (During Sitting or Standing) Using a Simple, Inexpensive Device (Approximately $20)

- In Contrast to Spirometry, Applying Quality Control to Peak Flow Measurements is Difficult Due to the Lack of Graphic Display to Ensure Appropriate Technique and Maximal Patient Effort (and the Lack of Ability to Calibrate Different Peak Flow Meters)

Limitations

- Peak flow values often underestimate the severity of airflow obstruction

- Significant airflow obstruction may be present on spirometry when the peak flow is within the normal range

- Reduced peak flow measurements may be seen in both obstructive and restrictive diseases. Spirometry and measurement of lung volumes are necessary to distinguish the two

- Peak flow measurements are not sufficient to distinguish upper airway obstruction (eg, vocal cord dysfunction) from asthma

- Spirometry with a flow-volume loop is needed for evaluation of upper airway obstruction

- The validity of PEF measurements depends entirely upon patient effort and technique

- Errors in performing the test frequently lead to underestimation of true values, and occasionally to overestimation

- Home PEF monitoring is unsupervised

- Patients may produce higher values in the clinician’s office with appropriate coaching to ensure a maximal effort

- Peak flow meters cannot be routinely calibrated, unlike spirometers

- Thus, results will vary somewhat between different instruments and the accuracy of a particular peak flow meter may deteriorate over time

Interpretation

- Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) Values are Generally Lower in the Early Morning (Due to Diurnal Variation)

- Average Normal Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) Values for Male/Female Adults are Based Upon Height and Age

- However, the Range of Normal Values Around the Mean is Wide (Up to 80-100 L/min), So Each Patient Must Establish Their Own Personal Best

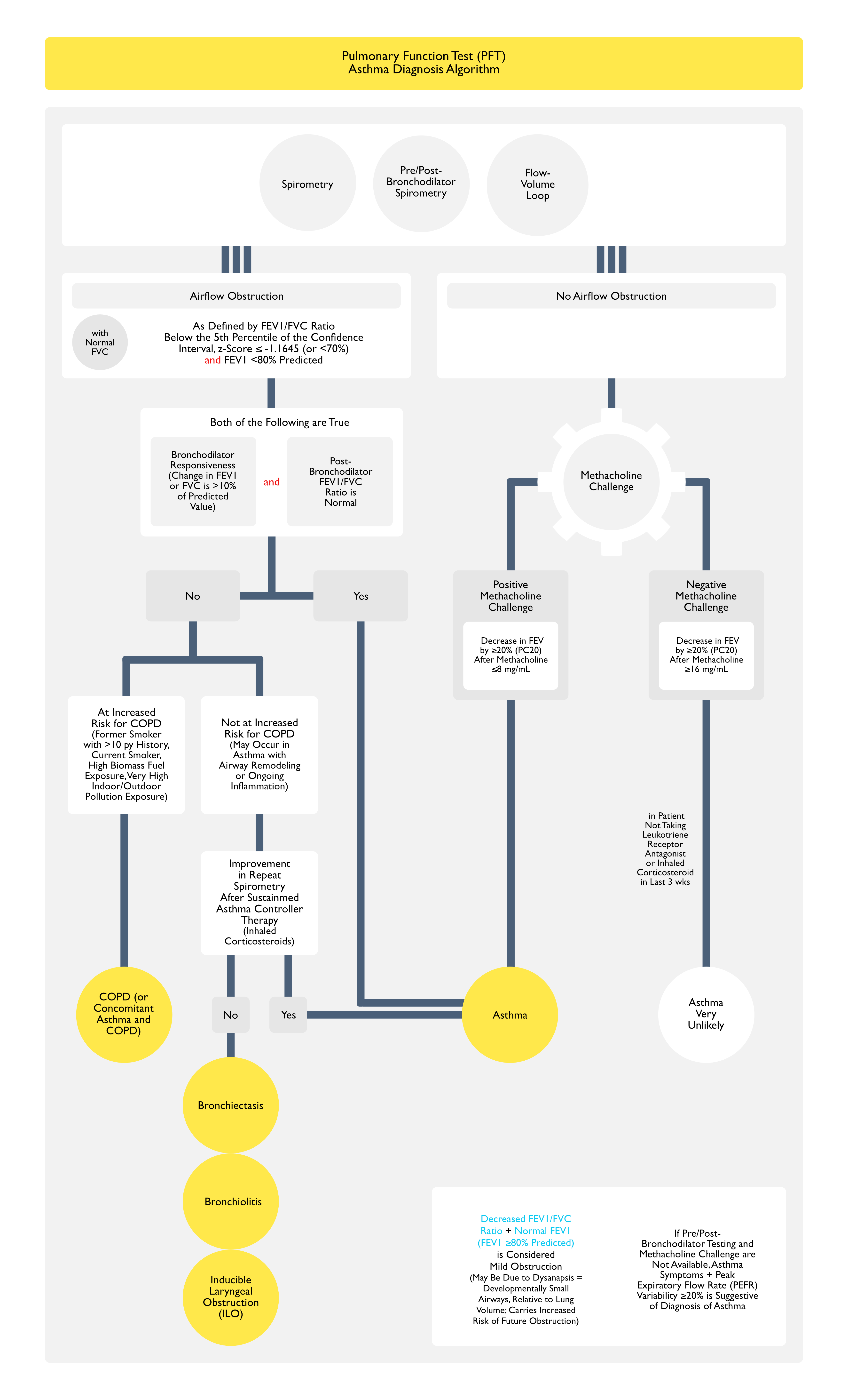

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFT’s) (see Pulmonary Function Tests)

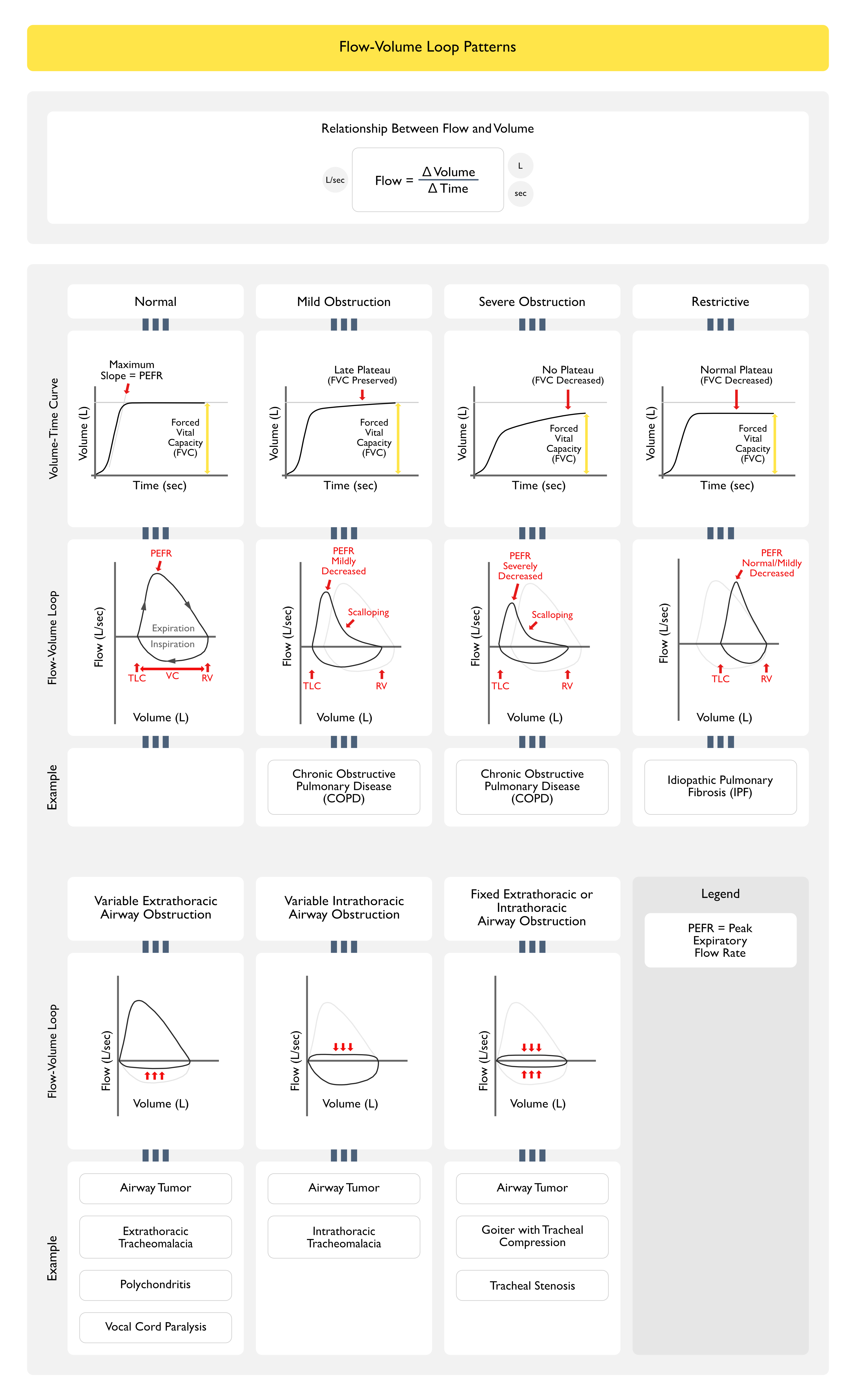

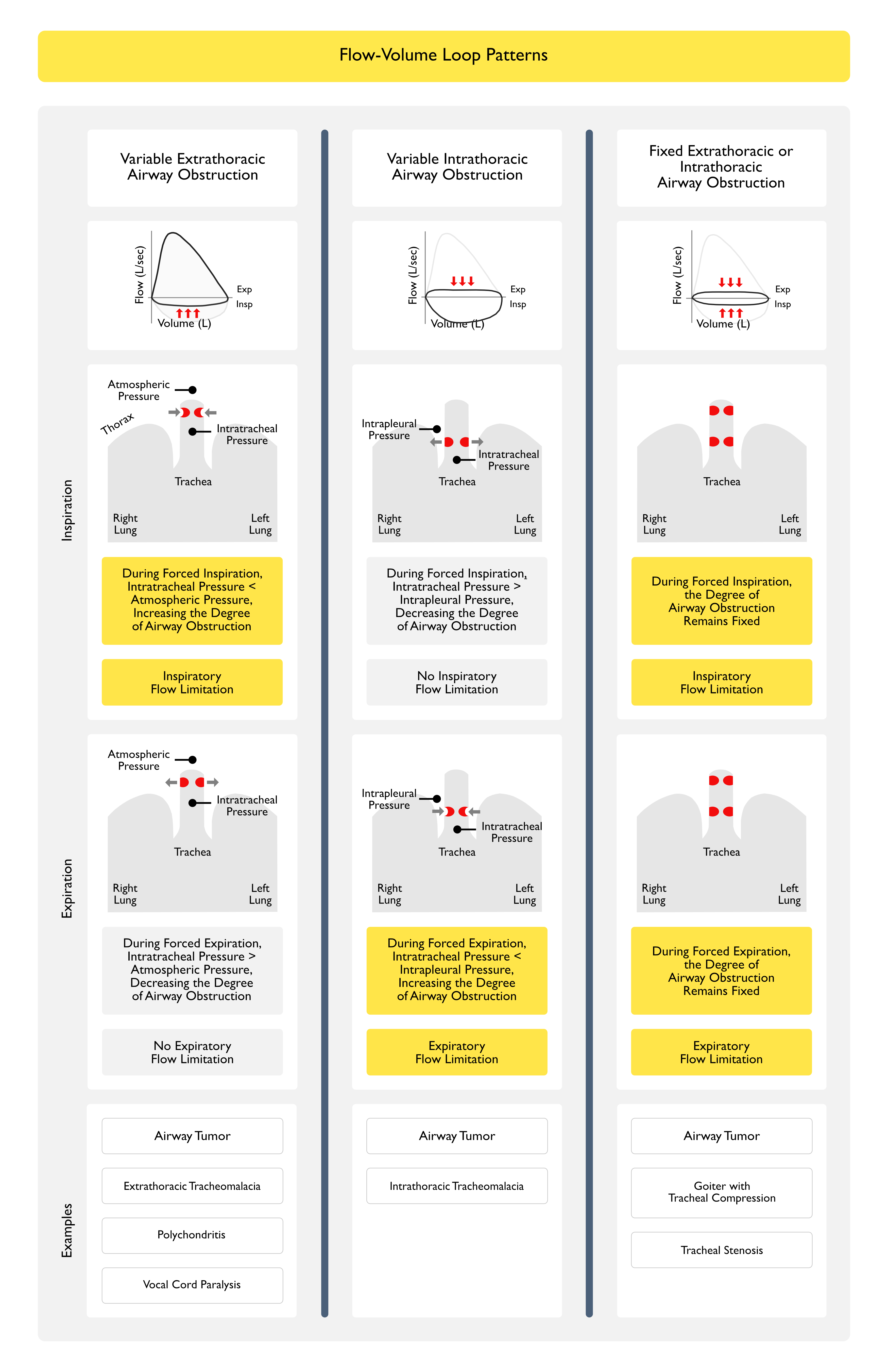

Flow-Volume Loop

- Rationale

- Obstructive Pattern Can Typically Be Identified Visually from the Shape of the Expiratory Flow-Volume Loop

- Scooped, Concave Appearance of the Expiratory Flow-Volume Loop Indicates Diffuse Intrathoracic Airflow Obstruction (Typical of Asthma, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/COPD, etc)

- Inspection of the Inspiratory and Expiratory Portions of the Flow-Volume Loop Can Also Be Useful in Identifying the Characteristic Patterns Observed in Upper Airway Obstruction

- Obstructive Pattern Can Typically Be Identified Visually from the Shape of the Expiratory Flow-Volume Loop

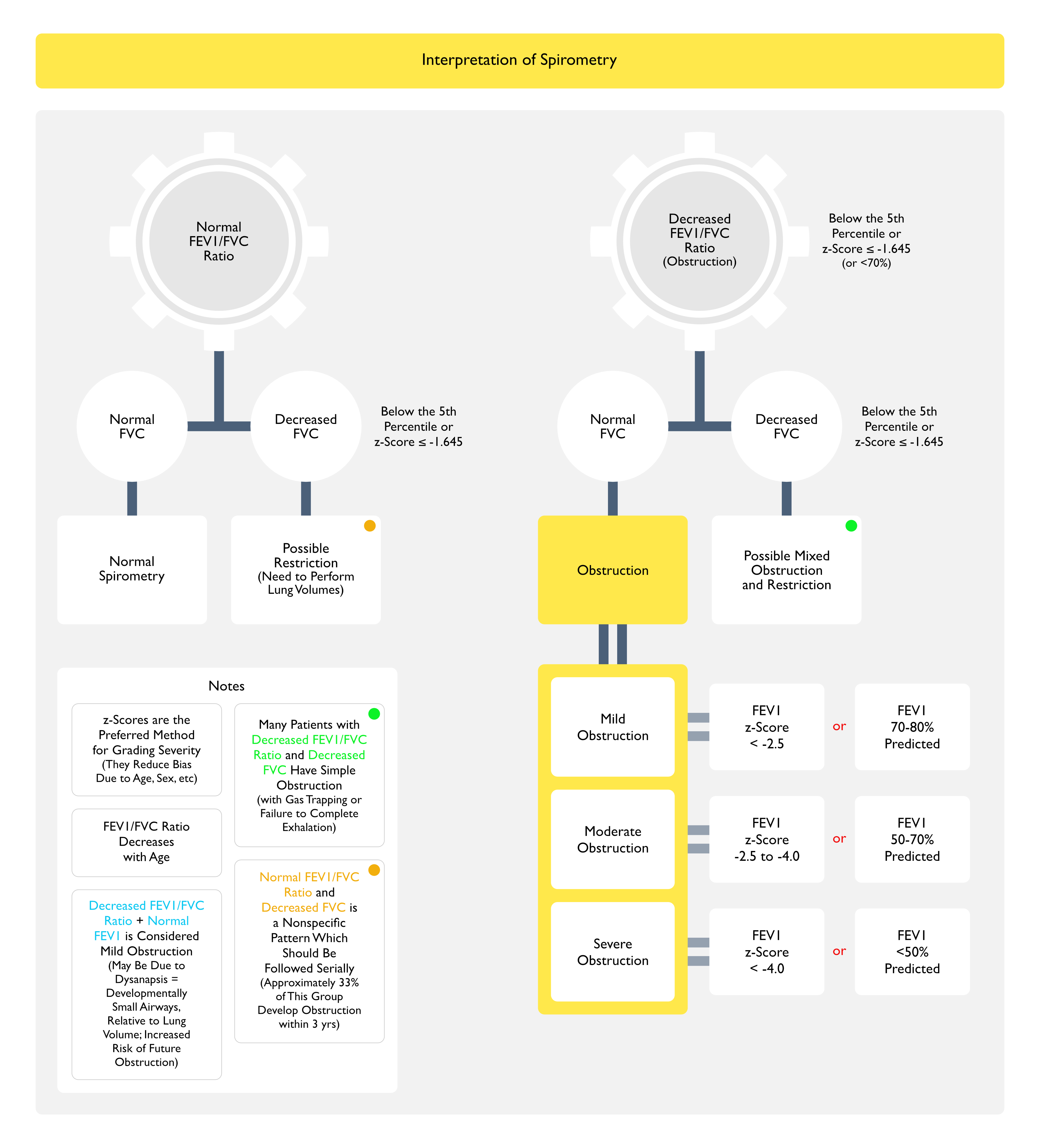

Spirometry

- Rationale

- Spirometry (Performed Pre-Bronchodilator and Post-Bronchodilator) is Critical for the Diagnosis of Asthma

- Spirometry is Useful for the Following in the Setting of Asthma

- Diagnosis of Baseline Airflow Obstruction (as Defined by Decreased FEV1/FVC Ratio)

- Characterization of the Severity of Airflow Obstruction (Based on the FEV1)

- Assessment of Reversibility of Airflow Obstruction (i.e. Bronchodilator Responsiveness)

- In Patients with Normal Airflow (i.e. Normal FEV1/FVC Ratio), Identification of a Restrictive Pattern (i.e. FVC <80% Predicted) Which Might Suggest the Presence of Another Lung Disease

- Technique

- Maximal Inhalation, Followed by a Rapid and Forceful Complete Exhalation into a Spirometer

- Measurement of Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second (FEV1) and Forced Vital Capacity (FVC)

- z-Scores are the Preferred Method for Grading Severity (They Reduce Bias Due to Age, Sex, etc)

- Due to the Fact that FEV1/FVC Ratio Decreases with Age

- Maximal Inhalation, Followed by a Rapid and Forceful Complete Exhalation into a Spirometer

- Interpretation

- Obstruction is Defined as an FEV1/FVC Ratio Below the Lower Limit of Normal (Cutoff Below the 5th Percentile of the Confidence Interval, Corresponding to a z-Score ≤ -1.645 or 70% Predicted)

- Note that the Absence of Obstruction Does Not Exclude the Diagnosis of Asthma, Since Airflow Obstruction in Asthma May Fluctuate Over Time

- In Patients with Airflow Obstruction (i.e. Decreased FEV1/FVC Ratio), the Severity of Airflow Obstruction is then Further Categorized by the Degree of Decrease in the FEV1 Below Normal

- Mild Obstruction

- FEV1 z-Score: more than -2.5

- FEV1 % Predicted (if z-Score is Not Available): 70-80%

- Moderate Obstruction

- FEV1 z-Score: -2.5 to -4.0

- FEV1 % Predicted (if z-Score is Not Available): 50-70%

- Severe Obstruction

- FEV1 z-Score: less than -4.0

- FEV1 % Predicted (if z-Score is Not Available): <50%

- Mild Obstruction

- Categories Do Not Necessarily Correlate with Asthma Symptoms or Severity

- Many Patients with Decreased FEV1/FVC Ratio and Decreased FVC Have Simple Obstruction (with Gas Trapping or Failure to Complete Exhalation)

- Normal FEV1/FVC Ratio and Decreased FVC is a Nonspecific Pattern Which Should Be Followed Serially

- Approximately 33% of This Group Develop Obstruction within 3 yrs

- Decreased FEV1/FVC Ratio + Normal FEV1 is Considered Mild Obstruction

- May Be Due to Dysanapsis (Developmentally Small Airways, Relative to Lung Volume)

- This Group is at Increased Risk of Future Obstruction

- In Some Patients with Severe Obstruction, the FEV1/FVC Ratio May Be Falsely Normal, Due to the Inability to Fully Exhale (i.e. Reach a Plateau on the Volume-Time Curve During Prolonged Expiration)

- This Leads to Underestimation of the True FVC

- Consequently, Interpretation of the FEV1/FVC Ratio without Evaluation of the Flow-Time Curves Can Inappropriately Rule Out Obstruction and Suggest Restriction (Eur Respir J, 2022) [MEDLINE]

- In Such Cases, When Lung Volume Measurements are Performed, the Severe Obstruction Generally Demonstrates Gas Trapping (as Evidenced by an Increase in Residual Volume or Increased Residual Volume/Total Lung Capacity Ratio >95th Percentile), or Even Hyperinflation (as Evidenced by Increased Functional Residual Capacity and/or Increased Total Lung Capacity)

- Obstruction is Defined as an FEV1/FVC Ratio Below the Lower Limit of Normal (Cutoff Below the 5th Percentile of the Confidence Interval, Corresponding to a z-Score ≤ -1.645 or 70% Predicted)

- Bronchodilator Responsiveness

- Technique

- Acute Reversibility of Airflow Obstruction is Assessed by Administering 2-4 puffs of a Short-Acting Bronchodilator (Albuterol), Preferably Using a Valved Holding Chamber (i.e. Spacer), and Then, Repeating the Spirometry 10-15 min Later

- Alternatively, Measurements Can Be Made Before and After Administration of a Nebulized Bronchodilator (Although is Uncommonly Performed)

- Acute Reversibility of Airflow Obstruction is Assessed by Administering 2-4 puffs of a Short-Acting Bronchodilator (Albuterol), Preferably Using a Valved Holding Chamber (i.e. Spacer), and Then, Repeating the Spirometry 10-15 min Later

- Interpretation

- According to the 2022 Guidelines, a Positive Bronchodilator Response Should Now Be Determined by a Change in FEV1 or FVC Compared with Their Reference-Equation Predicted Value, as Determined by the Following (Eur Respir J, 2022) [MEDLINE]

- Bronchodilator Response = ([Postbronchodilator Value – Prebronchodilator Value] x 100)/Predicted vValue, Where the Value is Either FEV1 or FVC

- An Increase of >10% in Value is Considered Significant

- Previously, an Increase of ≥12% and 200 mL in Either the FEV1 or FVC was Considered a Significant Bronchodilator Response (Eur Respir J, 2005) [MEDLINE]

- According to the 2022 Guidelines, a Positive Bronchodilator Response Should Now Be Determined by a Change in FEV1 or FVC Compared with Their Reference-Equation Predicted Value, as Determined by the Following (Eur Respir J, 2022) [MEDLINE]

- Use of Bronchodilator Responsiveness in the Diagnosis of Asthma

- In Isolation, the Presence of Bronchodilator Response is Not Sufficient to Make the Diagnosis of Asthma

- Bronchodilator Responsiveness Can Be Seen with Multiple Other Pulmonary Conditions (Such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease/COPD, Cystic Fibrosis/CF, Bronchiectasis, and Bronchiolitis)

- However, Asthma is More Likely than These Other Pulmonary Conditions to Yield a Large Increase in the FEV1 or FVC

- There is No Precise Cutoff Value Which Defines an Asthmatic Bronchodilator Response

- In a Large Study of Both Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Bronchodilator Responsiveness was Found to Be Associated with Lower Lung Function and Higher Symptom Burden in the Entire Group, But No Specific Cutoff Distinguished Asthma from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2024) [MEDLINE]

- As a Result, Bronchodilator Responsiveness Should Be Viewed as a Treatable Clinical Feature in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) (as Well as Other Airway Diseases), But Not as a Feature Specific to One Diagnosis

- Occasionally, Asthmatic Patients Will Demonstrate Spirometric Airflow Obstruction But Fail to Exhibit a Significant Improvement Bronchodilator Responsiveness (i.e. “False Negative Response”), Attributable to a Variety of Explanations

- Inadequate Bronchodilator Inhalation Due to Technical Issue with the Metered Dose Inhaler

- Recent Use of Short-Acting Bronchodilator (or Other Anti-Asthmatic Medication, Such as a Long-Acting Bronchodilator), Resulting in Near-Maximal Bronchodilation Prior to Testing

- Minimal Airflow Obstruction at the Time of Testing (i.e. FEV1 Already Close to 100%), Due to Impact of a Controller Medication or Normal Variation in Airflow During Asymptomatic Periods

- Irreversible Airway Obstruction in the Setting of Severe Asthma (Due to Chronic Inflammation or Scarring)

- In Addition, Spirometry May Be Normal in Asthmatic Patients without Active Symptoms

- Changes in the Forced Expiratory Flow Between 25-75% of the Vital Capacity (FEF25-75) Observed Over Time or in Response to Bronchodilator are Not Used to Diagnose Asthma in Adults (Nor are Decreases in the FEF25-75 Used to Characterize Asthma Severity)

- Technique

- Bronchoprovocation Testing

- Rationale

- Bronchoprovocation Testing is Useful to Diagnose Asthma in Patients with Normal Baseline Airflow

- Bronchoprovocation Testing Can Be Used to Identify or Exclude Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Patients with Atypical Presentations (Such as Normal Baseline Spirometry, No Variability in Airflow Obstruction with Serial Spirometry or Peak Flow) or Isolated Symptoms of Asthma (Especially Cough)

- Asthmatics are More Sensitive (“Hyperresponsive”) to Bronchoprovocation Stimuli than Patients without Asthma

- In Addition, the Percent Improvement Post-Bronchodilator After Bronchoconstriction May Predict a Propensity for Asthma Exacerbations (Eur Respir J, 2016) [MEDLINE]

- When Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction (ILO) (aka Paradoxical Vocal Cord Motion) is Being Considered in the Differential Diagnosis, an Inspiratory and Expiratory Flow-Volume Loop and Sometimes Also Fiberoptic Laryngoscopy are Performed During Bronchoprovocation Testing to Identify an Upper Airway Response Mimicking Asthma (see Inducible Laryngeal Obstruction)

- Relative Contraindication (Eur Respir J, 2017) [MEDLINE]

- FEV1 <60% (or <1.5 L)

- Technique

- Methacholine Challenge

- Most Commonly Used Bronchoprovocation Test

- Positive = FEV1 Decreased ≥20% (PC20) After ≤8 mg/mL

- Negative = FEV1 Decreased ≥20% (PC20) After ≥16 mg/mL

- Eucapnic Hyperventilation of Dry Air

- Exercise

- When a Diagnosis of Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction/Asthma is Suspected, Measuring Lung Function Before/After Exercise Can Be Performed

- In Patients without Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction/Asthma, FEV1 Increases with Exercise

- Therefore, a ≥10% Decrease in the FEV1 from Baseline is Consistent with Exercise-Induced Bronchoconstriction (Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2013) [MEDLINE]

- Post-Work Shift

- When a Diagnosis of Occupational Asthma is Suspected, Measuring Lung Function Before/After a Work Shift Can Be Performed

- Inhaled Mannitol (see Mannitol)

- Methacholine Challenge

- Interpretation

- Positive Bronchoprovocation Test (Indicating Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness) is Not Specific for Asthma

- A Cut Point of ≤8 mg/mL of Methacholine is Used to Indicate the Presence of Hyperresponsiveness, Since as Up to 5% of Normals (and a Greater Percentage of Non-Asthmatics with Rhinitis) Will Exhibit Positive Bronchoprovocation Test Results

- However, False-Negative Bronchoprovocation Test Results are Uncommon, and a Negative Test (i.e. No Significant Decrease in FEV1 at the Highest Methacholine Dose Administered) Performed in a Patient Off Asthma Therapy Reliably Excludes the Diagnosis of Asthma

- Positive Bronchoprovocation Test (Indicating Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness) is Not Specific for Asthma

- Rationale

Lung Volumes

- Physiologic Background

- At Total Lung Capacity (TLC), the Elastic Recoil of the Lungs is the Primary Determinant of the Driving Pressure for Expiratory Airflow During Passive Exhalation

- Therefore, a a Decrease in Total Lung Capacity (TLC) May Indicate an Increase in Recoil Whereas an Increase in Total Lung Capacity (TLC) May Indicate a Decrease in Recoil

- Lung Volume is an Important Determinant of Airways Caliber Via the Tethering Effect of Parenchymal Attachments

- At Total Lung Capacity (TLC), the Elastic Recoil of the Lungs is the Primary Determinant of the Driving Pressure for Expiratory Airflow During Passive Exhalation

- Rationale

- Lung Volumes are Not Required for the Diagnosis of Asthma, But May Be Useful to Exclude Other Lung Diseases Which May Present Diagnostic Confusion (Particularly Restrictive Lung Disease)

- Interpretation

- Residual Volume (RV)

- Increased Residual Volume (RV) (≥120% Predicted or Greater than the 95th Percentile) is the Most Consistently Abnormal of All the Lung Volumes in Asthma, and is the Last to Return to Normal Following Treatment

- However, Measurement of Residual Volume (RV) is Highly Variable, and a Value >150% Predicted is Required Before One Can Surmise that an Actually Abnormality Exists (Arch Intern Med, 1983) [MEDLINE]

- Mechanisms

- Poor Expiratory Effort

- Abnormal Closure of Airways (Which Can Be Confirmed by Observing a Decreased in Residual Volume (RV) Following Bronchodilator Therapy)

- Functional Residual Capacity (FRC)

- Functional Residual Capacity (FRC) Greater than the Upper 95th Percentile (Preferred) or ≥120% Predicted Indicates Gas Trapping

- Functional Residual Capacity (FRC) Me Be Increased in Asthma (Especially During the Acute Phase of an Asthma Exacerbation)

- Mechanisms

- Persistent/Tonic Activity of the Inspiratory Muscles (Am Rev Respir Dis, 1980) [MEDLINE]

- Clinical Implications

- The Increase in Functional Residual Capacity (FRC) is Important, Because Hyperinflation is Believed to Be Responsible for the Clinical Manifestations of Chest Tightness and Dyspnea (Chest, 2006) [MEDLINE]

- Total Lung Capacity (TLC)

- Total Lung Capacity (TLC) Greater than the Upper 95th Percentile (preferred) or ≥120% Predicted Indicates Hyperinflation

- In Asthma, the Total Lung Capacity (TLC) May Be Normal or Elevated, Although an Elevated Total Lung Capacity (TLC) is More Commonly Observed in the Setting of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Mechanisms (Am J Med, 1976) [MEDLINE]

- Loss of Lung Elastic Recoil

- Increased Outward Recoil of the Chest Wall

- Increased Inspiratory Muscle Strength

- Clinical Implications

- Elevation in the Total Lung Capacity (TLC) is Usually Associated with More Severe Airflow limitation or asthma of longer duration

- Residual Volume (RV)/Total Lung Capacity (TLC) Ratio

- Use of RV/TLC Ratio or FRC/TLC Ratio Can Be Helpful in Patients for Whom Predicted Values of the Individual Measurements are Less Reliable (Such as in Young Children, Patients with Unusual Ethnic Origins, etc)

- In Asthma, the RV/TLC Ratio is Generally Increased (Indicative of Gas Trapping) But Must Be >150% Predicted Before it Can Be Considered to Be Abnormal

- Residual Volume (RV)

Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO)

- Rationale

- Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) Measures the Ability of the Lungs to Transfer Gas from Inhaled Air to the Red Blood Cells in Pulmonary Capillaries

- Normal-Increased

- In Patients with Asthma, the Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) is Usually Either Normal or High, and the Degree of Elevation is Related to Asthma Severity

- Mechanisms

- Increased Negative Intrathoracic Pressure During Inspiration, Resulting in Increased Pulmonary Capillary Bloow Flow

- Improved Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) Matching, Due to Increased Apical Lung Perfusion

- Hemoglobin Extravasation, Due to the Inflammatory Process (Although Evidence for This Mechanism is Limited)

- In Patients with Asthma, the Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) is Usually Either Normal or High, and the Degree of Elevation is Related to Asthma Severity

Skin Testing

- To aeroallergens from 4 groups: mites and cockroaches/animals/pollens/molds): many allergens within each group cross-react (severe reaction to one untested allergen is unusual)

Sputum Gram Stain/Culture (see Sputum Culture)

- Disease activity may correlate with number of eosinophils (Charcot-Leyden crystals, from degeneration of eos may be seen) and epithelial cells (Curschmann’s spirals or Creola bodies: epithelial cells in sputum, suggests severe attack)