Epidemiology

US Incidence of Tuberculosis

- Peaked US case-rate in 1992, declined since then, now case-rates are at an all-time low

- New York City has 15% of all TB cases in the US (but has >60% of all the MDR tuberculosis cases in US)

Global Incidence of Tuberculosis

- Global case-rates are at an all-time high

- Over 33% of the world’s population infected with TB

- Eight million new cases of TB diagnosed worldwide annually

- Over 2 million TB-related deaths occur annually

- WHO TB control program (DOT, short-course) has been effective in some areas, it is much less effective in areas where HIV is prevalent

Epidemiology of Tuberculosis Pleuritis

- Annual incidence of TB pleuritis is about 1,000 in US

- Only 1 in 30 cases of TB in USA are TB pleuritis (without much change in AIDS era)

- Much higher incidence in Rwanda: 86% of cases of TB present with pleural effusion

- TB is the most common cause of exudative effusion in many parts of world (accounts for a only a minority of exudate cases in the USA)

- TB Pleuritis Occurs As:

- Post-Primary TB Pleuritis: occurs 6 weeks-6 months after primary TB infection

- Reactivation TB Pleuritis:

- Age: patients with TB pleuritis are generally younger (mean age = 28 y/o) compared to patients with parenchymal TB (mean age = 54 y/o)

- Reactivation TB pleuritis cases tend to be older than post-primary TB pleuritis cases

- Effect of HIV Infection on TB Pleuritis: although counterintuitive, HIV cases of TB have higher incidence of TB pleuritis than normals with TB (TB pleuritis occurs in 29% of HIV TB cases in USA; Kramer, 1990)

Risks of Tuberculosis Transmission During Air Travel

- Due to air circulation pattern in modern planes (air circulates from top to bottom, not fore and aft), risk is limited to those sitting within a few rows of an infected passenger

- No cases of transmission from passenger to flight attendant have been documented (although there have been cases of transmission from attendant to attendant)

Risk Factors for Tuberculosis (Adapted from Lancet, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Advanced Age

- Epidemiology: major risk factor for acquisition, disease progression, form of disease, and mortality risk

- African-American Race

- Epidemiology:

- Alcohol Abuse (see Ethanol)

- Epidemiology: approximate 3x-increased risk of disease with consumption of >40 g/day

- Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (Anti-TNFα) Therapy (see Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Therapy) [MEDLINE]

- Epidemiology: 1.5x-increased risk in rheumatology patients in North America

- Relative Risk: infliximab > adalimumab > etanercept

- Risk is Greater with Anti-TNFα Antibodies Than with Soluble TNFα Receptor

- Median Time to Diagnosis: 12 wks after starting therapy (and 69% of cases had 3 or fewer infusions)

- Clinical

- 56% of cases had extrapulmonary TB

- 25% of cases had disseminated TB

- Cardiac Conditions with Decreased Pulmonary Perfusion

- Pulmonary Artery Stenosis (see Pulmonary Artery Stenosis)

- Tetralogy of Fallot (see Tetralogy of Fallot)

- Chronic Corticosteroid Use (see Corticosteroids)

- Epidemiology: approximate 10x-increased risk of TB in rheumatology patients in North America

- However, Short Courses of Corticosteroids (Such as for PCP Treatment) Do Not Increase the Risk for TB

- Epidemiology: approximate 10x-increased risk of TB in rheumatology patients in North America

- Diabetes Mellitus (DM) (see Diabetes Mellitus)

- Epidemiology: approximate 3x-increased risk of TB (especially in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus)

- Prognosis: TB in the setting of diabetes mellitus is associated with an increased mortality rate

- End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) (see Chronic Kidney Disease)

- Epidemiology: >10x-increased risk of TB

- Genetic Risk Factors: various genes have been associated with increased risk of TB

- Interferon γ Gene

- Mannan Binding Lectin Gene

- Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein 1 Gene

- Nitric Oxide Synthase 2A Gene

- Toll-Like Receptor Genes

- Vitamin D Receptor Gene

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Tuberculosis is the Leading Cause of Death Among HIV Patients

- In Addition, Tuberculosis-Related Adverse Events, Anti-Tuberculous Drug Absorption/Metabolism, and Anti-Tuberculous Drug Interactions May Be Unique in This Patient Population

- Indoor Air Pollution (see Air Pollution)

- Epidemiology: approximate 2x-increased risk of TB (weak evidence)

- Intravenous Drug Abuse (see Intravenous Drug Abuse)

- Epidemiology:

- Low Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Epidemiology: increased risk of TB

- Low CD4 Count

- Epidemiology: independent risk factor (apart from HIV)

- Malignancy

- Epidemiology: increased risk of TB with both solid organ and hematologic malignancies

- Specific Malignancies

- Hairy Cell Leukemia (see Hairy Cell Leukemia): due to decreased monocyte count

- Malnutrition (see Malnutrition)

- Epidemiology: increased risk of TB

- Overcrowded Living Conditions

- Epidemiology: increased risk of TB

- Physiology increased exposure to infectious cases

- Male Sex

- Epidemiology: M:F ratio is 2:1 in adults (but not in children)

- Silicosis (see Silicosis)

- Epidemiology: approximate 3x-increased risk of TB has been reported in South African gold miners with silicosis

- Tobacco Abuse (see Tobacco)

- Epidemiology: approximate 2x-increased risk of infection, progression to tuberculosis disease, and death

- Tofacitinib (Xeljanz) (see Tofacitinib)

- Epidemiology: xxx

- Physiology: xxx

- Vitamin D Deficiency (see Vitamin D)

- Epidemiology: increased risk of TB

Use of Anti-TNFα Medications in Populations at Risk for Developing TB

- The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published recommendations in 2005 for the prevention of TB when anti-TNF-α agents are used

[Winthrop KL, Siegel JN, Jereb J, et al. Tuberculosis associated with therapy against tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52:2968- 2974] - All patients should be carefully screened for risk factors for M tuberculosis, including birth or residence in an endemic area; history of residence in a congregate setting, such as a prison, homeless shelter, or chronic care facility; use of illicit drugs; and work in a health-care environment.

- Tuberculin skin testing should be performed unless there is a known history of positive reactivity

- Controversy exists about when anti-TNF-α therapy can be initiated, but the general consensus is that it can be introduced 1 to 2 months after the start of prophylactic therapy. The protection, however, is not complete, as TB has been reported despite prophylaxis. A high degree of suspicion should be maintained in all individuals receiving anti-TNF-α therapy, especially if any febrile or respiratory illness develops.

Microbiology

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: xxx

Physiology

- TNFα promotes the killing of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis through activation of macrophages

- TNFα plays a role in the formation and maintenance of granulomas

- Almost all cases of TB are due to airborne particle transmission (as few as 1-5 mycobacteria deposited in the terminal alveoli are required for infection)

-Disease Progression: some infected persons may develop primary TB

–TB organisms remains present but inactive and may cause reactivation TB later

–5% of patients wth latent disease wil develop active TB within 2 yrs and an additional 5% will develop active TB at a later time

–Although most TB is due to reactivation, cases of exogenous reinfection with a second strain of TB can occur

-TB pleuritis: results from rupture of a subpleural caseous focus into the pleural space with delayed hypersensitivity reaction

–Anti-lymphocyte serum blocks effusion development in animal models

–AFB burden is low and T-cells sensitized to tuberculous protein are present in TB pleuritis pleural fluid

–Some patients have a sequestration of PPD-reactive T-cells in pleural space or some have circulating adherent cells that suppress the circulating sensitized T-cells (these may explain 30% rate of PPD-negativity in TB pleuritis)

–Role of Delayed Hypersensitivity: mice immunized (in footpad) with TB protein (killed TB bacilli) develop pleural effusions when they receive intrapleural PPD 3-5 weeks later

—Development of effusions is inhibited by treatment anti-lymphocyte serum

—Neutrophils invade pleural space early (within the first 24 hrs) -> recruitment of monocytes (between day 2-5) -> lymphocyte predominance (they respond to PPD only after day 5) -> inflammation causes impaired lymphatic clearance of protein from pleural space

Diagnosis

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) (see Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate)

- Elevated in 70% of Miliary Tuberculosis Cases

Serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP) (see Serum C-Reactive Protein)

- Commonly Elevated in Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis: CRP was found to be positive in 85% of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis (Int J Tuberc Lung Dis, 2008) [MEDLINE]

Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) (see Tuberculin Skin Test)

General Comments

- Rationale

- Detects the presence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis infection

- Type IV T Cell-Mediated Hypersensitivity Reaction is Detectable 2-8 wks After Infection (see Immune Hypersensitivity)

- Technique: Mantoux technique injection of 0.1ml of 5 TU purified protein derivative (PPD) solution

- Reading of Test by Health Care Professional: within 48-72 hrs

- Indications

- Children <5 y/o: preferred test for latent tuberculosis

- Contraindications

- Prior Positive TST

- Prior Treatment for Tuberculosis

Tuberculin Skin Testing (TST) of Contact of Patient with Infectious Tuberculosis

- TST or IGRA Should Be Performed in All Contacts

- If Initial TST or IGRA is Negative, Retesting in 8-10 wks After Exposure Has Ended is Recommended

- Note: this is not considered two-step TST testing, as the initial test may have been to early to detect the infection

- TST or IGRA Should Be Performed in Children <5 y/o or Immunocompromised (HIV, etc)

- If Initial TST or IGRA is Negative, Chest X-Ray (CXR) Should Be Performed

- If CXR is Normal, Repeat TST or IGRA Should Be Performed 8-10 wks After Exposure Has Ended (with Same Test) and Treatment Should Be Started for Latent Tuberculosis

- If Repeat TST or IGRA is Now Positive, Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Should Be Continued

- If Repeat TST or IGRA is Negative, Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Can Usually Be Discontinued

Tuberculin Skin Testing (TST) in Pregnancy (see Pregnancy)

- TST is Safe and Reliable Throughout Pregnancy

- TST or IGRA Testing Should Be Performed Only if Specific Risk Factors are Present for Latent Tuberculosis or for Progression of Latent Tuberculosis to TB Disease

- If TST or IGRA is Positive, CXR (with Proper Shielding) Should Be Performed

Two-Step Tuberculin Skin Testing (TST)

- Rationale: some patients with prior TB infection may have a negative TST if many years have passed since their initial infection

- “Booster Phenomenon”: initial TST is negative, becoming positive on the second TST due to the initial TST stimulating immune reactivity to the second TST (note, booster phenomenon may be incorrectly interpreted to be a new conversion)

- Two-Step TST Testing is Recommended at the Time of Initial Testing for Patients Who May Be Tested Periodically (Health Care Workers, etc)

- If the First TST is Positive, the Patient is Infected and Should Be Treated Accordingly

- If the First TST is Negative, Second TST Should Be Performed 1-3 wks Later

- If Second TST is Positive, the Patient is Infected and Should Be Treated Accordingly

- If Second TST is Negative, the Patient is Considered Not Infected

Interpretation of Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) (Per CDC Recommendations, Accessed 9/16) [LINK]

- General Comments

- Interpretation of TST is the Same for Patients Who Have Received Prior BCG Vaccination (see Bacillus Calmette-Guerin)

- The Majority of BCG Cross-Reactivity with TST Wanes Over Time

- However, Periodic TST May Prolong (Boost) Reactivity in Vaccinated Persons

- Regardless, a Patient with a History of BCG Vaccination Can Be Tested and Treated for Latent Tuberculosis if They React to the TST

- Interpretation of TST is the Same for Patients Who Have Received Prior BCG Vaccination (see Bacillus Calmette-Guerin)

- TST ≥5 mm Induration is Considered Positive in the Following

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Fibrotic Changes on Chest X-Ray Consistent with Prior Tuberculosis

- Organ Transplant or Other Immunosuppression

- Including Patient on Corticosteroids with the Equivalent of Prednisone ≥15 mg/day x ≥1 mo (see Corticosteroids)

- Including Patient on Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (Anti-TNFα) Therapy (see Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Therapy)

- Recent Contact of Person with Infectious Tuberculosis Disease

- TST ≥10 mm Induration is Considered Positive in the Following

- Children <4 y/o

- Condition Which Increases the Risk for Progression of Tuberculosis Disease

- Infants/Children/Adolescents Exposed to Adults in Hig-Risk Categories

- Intravenous Drug Abuse (IVDA) (see Intravenous Drug Abuse)

- Mycobacteriology Lab Personnel

- Recent Arrival to US Within the Last 5 Years from High-Prevalence Region

- Resident/Employee of High-Risk Setting

- Correctional Facility

- Homeless Shelters

- Hospital/Health Care Facility

- Long-Term Care Facility

- Residential Facility for Patients with HIV/AIDS

- TST ≥15 mm Induration is Considered Positive in the Following

- Patient with No Known Risk Factor for Tuberculosis

- The natural history of untreated pulmonary tuberculosis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(4):367-379. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00097-8 [MEDLINE]

- Stages of tuberculosis disease can be delineated by radiology, microbiology, and symptoms, but transitions between these stages remain unclear. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of individuals with untreated tuberculosis who underwent follow-up (34 cohorts from 24 studies, with a combined sample of 139 063), we aimed to quantify progression and regression across the tuberculosis disease spectrum by extracting summary estimates to align with disease transitions in a conceptual framework of the natural history of tuberculosis. Progression from microbiologically negative to positive disease (based on smear or culture tests) in participants with baseline radiographic evidence of tuberculosis occurred at an annualised rate of 10% (95% CI 6·2-13·3) in those with chest x-rays suggestive of active tuberculosis, and at a rate of 1% (0·3-1·8) in those with chest x-ray changes suggestive of inactive tuberculosis. Reversion from microbiologically positive to undetectable disease in prospective cohorts occurred at an annualised rate of 12% (6·8-18·0). A better understanding of the natural history of pulmonary tuberculosis, including the risk of progression in relation to radiological findings, could improve estimates of the global disease burden and inform the development of clinical guidelines and policies for treatment and prevention

Interferon–γ Release Assay (IGRA)

General Comments

- Rationale: detects the presence of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis infection

- Indications

- Populations with Poor Rate of Return for TST Reading and Interpretation: such as the homeless, etc

- History of Prior BCG Vaccination (see Bacillus Calmette-Guerin)

- IGRA Tests Use Antigens Which Do Not Cross-React with BCG: therefore, BCG does not cause false-positives in IGRA’s

- Prior to Initiation of Immunosuppressive Therapy

- Methotrexate (see Methotrexate) and Other Immunosuppressives

- Commercially-Available Assays

- QuantiFERON®-TB Gold-in-Tube Test (QFT-GIT): interpretation (qualitative and quantitative) is based on the amount of interferon–γ that is released

- T-SPOT® TB Test: interpretation (qualitative and quantitative) is based on the number of cell which release interferon–γ

- Advantages

- Does Not Cause Booster Phenomenon

- Interpretation is Not Subjective

- Only Single Visit Required to Conduct the Test

- Result Available within 24 hrs

- Unaffected by BCG and Most Environmental Mycobacteria (see Bacillus Calmette-Guerin)

- Disadvantages

- Limited Data on Use in Specific Groups (Children <5 y/o, Persons Recently Exposed to TB, Immunocompromised Patients, and Those Who Will Be Serially Tested)

- Sample Must Be Processed within 8-30 hrs After Collection

Interferon–γ Release Assay (IGRA) Testing of Contacts of Patient with Infectious Tuberculosis

- TST or IGRA Should Be Performed in All Contacts

- If Initial TST or IGRA is Negative, Retesting in 8-10 wks After Exposure Has Ended is Recommended

- Note: this is not considered two-step TST testing, as the initial test may have been to early to detect the infection

- TST or IGRA Should Be Performed in Children <5 y/o or Immunocompromised (HIV, etc)

- If Initial TST or IGRA is Negative, Chest X-Ray (CXR) Should Be Performed

- If CXR is Normal, Repeat TST or IGRA Should Be Performed 8-10 wks After Exposure Has Ended (with Same Test) and Treatment Should Be Started for Latent Tuberculosis

- If Repeat TST or IGRA is Now Positive, Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Should Be Continued

- If Repeat TST or IGRA is Negative, Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Can Usually Be Discontinued

Interferon–γ Release Assay (IGRA) Testing in Pregnancy

- TST or IGRA Testing Should Be Performed Only if Specific Risk Factors are Present for Latent Tuberculosis or for Progression of Latent Tuberculosis to TB Disease

- If TST or IGRA is Positive, CXR (with Proper Shielding) Should Be Performed

Sputum Acid Fast Bacteria (AFB) Stain and Culture (see Sputum Culture)

- Indications

- Positive Results for TB Infection and Either an Abnormal CXR or Presence of Respiratory Symptoms (with Normal CXR)

Technique

- Expectorated Sputum

- Induced Sputum: using 3-5% hypertonic saline via an ultrasonic nebulizer

- Sample Which Results is Thin and Resembles Saliva

- Usually Well-Tolerated: although it may induce bronchospasm in some patients

- Acid-Fast Staining/Smear

- Sensitivity: capable of detecting 10,000 bacilli/mL (if 100 oil immersion fields are examined)

- Sensitivity is Increased by Concentration Via Centrifugation or Chemical Processing with Sedimentation

- Sensitivity is Increased Approximately 10% by Using a Fluorochrome Staining Procedure with Auramine O (Which Fluoresces)

- Sensitivity: capable of detecting 10,000 bacilli/mL (if 100 oil immersion fields are examined)

- Mycobacterial Culture in Liquid Media

- Sensitivity: capable of detecting as few as 10-1000 viable mycobacteria/mL

Frequency of Positive Acid-Fast Bacteria (AFB) Smear/Culture in Miliary Tuberculosis (Am J Med, 1990) [MEDLINE]

- Sputum (see Sputum Culture)

- Smear: 33% positive

- Culture: 62% positive

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) (see Bronchoscopy)

- Smear: 27% positive

- Culture: 55% positive

- Gastric Aspirate (see Nasogastric Tube)

- Smear: 43% positive

- Culture: 100% positive

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) (see Lumbar Puncture)

- Smear: 8% positive

- Culture: 60% positive

- Urine (see Urine Culture,)

- Smear: 14% positive

- Culture: 33% positive

- Serosal (Ascites, Pleural, Pericardial)

- Smear: 6% positive

- Culture: 44% positive

Clinical Efficacy

- Screening of Immigrants and Refugees Bound for the United States with New Culture-Based Method Introduced by CDC in 2007 (Instead of the Prior Smear-Based Method) (Ann Intern Med, 2015) [MEDLINE]

- Main Findings: implementation of the culture-based algorithm may have substantially reduced the incidence of TB among newly arrived, foreign-born persons in the United States

- xxx

- Abandon the Acid-Fast Bacilli Smear for Patients With TB on Effective Treatment. Chest. 2023 Jul;164(1):21-23. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.02.006 [MEDLINE]

- https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(23)00186-1/fulltext

Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAAT)

- Rationale: use amplification of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis RNA or DNA in specimen

- Allow Detection Where Organisms are Present in Too Small of Quantity to Be Detected by Routine Staining Techniques

- Samples Used

- Blood

- Sputum

- Urine

- Commercially-Available Assays: allow diagnosis within 24 hrs

- Amplified MTD Test (GenProbe): FDA-approved for both smear-negative and smear-positive sputum or bronchoscopy samples

- Amplicor (Roche): FDA-approved only for smear-positive sputum or bronchoscopy samples

Xpert MTB/RIF Assay

- Samples Used

- Sputum: FDA-approved for use on sputum in adults

- Lymph Nodes: may be used

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF): may be used

- Pleural Fluid: sensitivity is low (46%) for pleural fluid samples

- Assay Can Simultaneously Identify Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Detect Rifampin Resistance

Clinical Manifestations-Latent Tuberculosis

Risk of Progression for Latent Tuberculosis to Tuberculosis Disease

- Risk of Progression from Latent Tuberculosis to Tuberculosis in Normal Patients: 10% over lifetime

- Risk of Progression from Latent Tuberculosis to Tuberculosis Disease in Patients with Untreated HIV (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus): 7-10% per year

- Risk of Progression is Decreased with Antiretroviral Therapy, But Still Remains Higher Than the Risk of Progression in Normal Patients

Recommendations for Chest X-Ray (CXR) in the Setting of Latent Tuberculosis (see Chest X-Ray) (Per CDC Recommendations, Accessed 9/16) [LINK]

- CXR Should Be Performed for a Patient with Positive TST or IGRA

- CXR Should Be Performed in the Absence of a Positive TST or IGRA When a Patient is a Close Contact of an Infectious TB Patient and Treatment for Latent Tuberculosis Will Be Started (“Window Prophylaxis” in a Young Child or Immunocompromised Patient)

- Children <5 y/o Should Have Both Posterior-Anterior and Lateral Views; All Others Should Have at Least Posterior-Anterior Views

- Persons with Nodular/Fibrotic Lesions Consistent with Old TB are High-Priority Candidates for Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis After TB Disease is Excluded

- Persons with Fully Calcified, Discrete Granulomas Do Not Have an Increased Risk for Progression to TB Disease

Recommendations for Latent Tuberculosis Testing in the Setting of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- HIV-Infected Patients Should Be Initially Tested for Latent Tuberculosis Infection (with TST or IGRA)

- A Negative TST or IGRA Does Not Exclude Latent Tuberculosis in this Population (As They May Have a Compromised Ability to React to These Tests)

- Annual Testing Should Be Considered for HIV Patients Who are Negative for Latent Tuberculosis on Initial Evaluation and Who Have a Risk for Exposure to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis

- Anergy Testing in HIV Patients Has Unclear Utility: not recommended

- HIV-Infected Patients Started on Antiretroviral Therapy Who Were Initially Negative Should Be Retested for for Latent Tuberculosis: antiretroviral may have restored the immune response

Clinical Manifestations-Primary Tuberculosis

General Comments

- Definition of Primary Tuberculosis: new tuberculosis infection or active tuberculosis disease occurring in a previously naive host

- Primary Tuberculosis was Historically a Childhood Disease

- However, Since the Introduction of Isoniazid Therapy in the 1950’s, There Has Been an Increased Frequency of Primary Tuberculosis in Adolescent/Adult Populations

Pulmonary Manifestations (Acta Tuberc Scand, 1957) [MEDLINE]

General Comments

- Incidence of Pulmonary Manifestations in Primary Tuberculosis: present in approximately 33% of primary tuberculosis cases

- Following Primary Tuberculosis Infection, 90% of Patients with Normal Immunity Will Control Further Replication of the Organism, Leading to Latent Tuberculosis

- The Remaining 10% of Patients Will Develop a Tuberculous Pneumonia at the Site of the Initial Infection or Near the Hilum, Develop Hilar Lymphadenopathy, or Develop Remote Disease (Cervical Lymphadenopathy, Meningitis, Pericarditis, Miliary Tuberculosis): risk factors for progression of local disease or dissemination include HIV infection, chronic kidney disease, poorly-controlled diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and older age

Cough (see Cough)

- Epidemiology

- May Occur

Hilar/Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy (see Mediastinal Mass)

- Hilar Lymphadenopathy is the Most Common Finding in Primary Tuberculosis: occurs in 65% of cases

- Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy May Result in Extrinsic Airway Compression (Especially in Children)

- Time Course of Hilar Lymphadenopathy

- Present as Early as 1 wk After Tuberculin Skin Test Conversion

- Present within 2 mo in All Cases

Exudative Pleural Effusion (Tuberculous Pleuritis) (see Pleural Effusion-Exudate)

- Epidemiology

- In Many Parts of the World, Tuberculosis is the Most Common Etiology of Exudative Pleural Effusion

- However, in the US, Only 7549 Cases of Tuberculous Pleuritis Were Reported Between 1993-2003 (Accounting for Only 3.6% of the Total Tuberculosis Cases Seen in This Period)

- Tuberculous Pleuritis Can Occur as a Manifestation of Primary Tuberculosis or as a Manifestation of Reactivation Tuberculosis

- Tuberculous Pleuritis Due to Primary Tuberculosis: pleural effusion occurs in 33% of primary tuberculosis cases

- Tuberculous Pleuritis Due to Reactivation Tuberculosis

- Controversial Whether HIV Increases the Incidence of Tuberculous Pleuritis: studies conflict (however, the incidence of tuberculous pleuritis is higher in HIV patients with CD4 >200/μL than in those with CD <200/μL, consistent with its purported hypersensitivity-related mechanism)

- Analysis of TB Surveillance Data from 1993-2003 (Chest, 2007) [MEDLINE]

- Annual Proportion of Pleural Tuberculosis Cases Remained Constant (Pleural Tuberculosis Accounted for 3.6% of All Tuberculosis Cases)

- Pleural Tuberculosis Occurred Significantly More Often than Pulmonary Tuberculosis Among Persons ≥65 y/o

- Pleural Tuberculosis Occurred Significantly Less Often than Pulmonary Tuberculosis Among Children <15 y/o and Adults 45-64 y/o

- Drug-Resistance Patterns of Pleural Tuberculosis Broadly Reflected Those of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: however, isolates from pleural tuberculosis patients were less often resistant to at least isoniazid (6.0% vs 7.8%) and to at least one first-line tuberculosis drug (9.9% vs 11.9%), as compared with pulmonary TB patients

- In Many Parts of the World, Tuberculosis is the Most Common Etiology of Exudative Pleural Effusion

- Physiology: delayed hypersensitivity reaction

- Diagnosis

- Pleural Fluid Characteristics

- Straw-Colored Appearance: usually

- Lymphocytic Cell Differential: usually

- Approximately 11% are Neutrophil-Predominant (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]: neutrophilic predominance is more common early in the course of disease, in the first 2 wks

- Occasional Pleural Eosinophils: although eosinophils >10% (in the absence of pneumothorax or prior thoracentesis) excludes the diagnosis of tuberculous pleuritis

- Low Numbers of Mesothelial Cells

- Normal-Decreased Pleural Fluid Glucose

- Elevated Total Pleural Fluid Protein: total protein >5.0 g/d/L is suggestive of tuberculous pleuritis

- Elevated Pleural Fluid Adenosine Deaminase (ADA) (“Large Form” is Released from T-Cells)): may be useful (>70 U/L suggests tuberculous pleuritis, while level <40 U/L usually rules out tuberculous pleuritis)

- Approximately 7% of Cases Have a Normal Pleural ADA Level (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Elevated Adenosine Deaminase is Also Seen in Many Empyemas, Some Malignancies, and Most Sases of RA (All of These Have “Small Form” >> “Large Form” of the Enzyme)

- Elevated Pleural Fluid Interferon-γ: may be useful (always >2.3 U/mL (mean is 91.2 U/mL), as compared to levels <2.0 U/mL in other diagnoses)

- Pleural Fluid PCR for Mycobacterial DNA: may be positive

- Induced Sputum Culture: positive in 50% of cases (reflecting the microscopic foci of pulmonary infection which likely accompany many tuberculous pleural effusions)

- Chest CT

- Usually Unilateral

- Approximately 9-10% of Cases are Bilateral (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Usually Small-Moderate in Size

- Approximately 8% of Cases Have an Opacified Hemithorax (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Approximately 86% of Cases Have Coexistent Parenchymal Infiltrates, with the Pleural Effusion Usually on the Same Side as the Infiltrate (Chest, 2006) [MEDLINE]

- Even in the Absence of Overt Parenchymal Disease, There is Likely Microscopic Lung Involvement (Induced Sputum Cultures are Positive in the Same Percentage of Cases with/without a Parenchymal Infiltrate)

- Usually Unilateral

- Pleural Fluid Culture: positive in only 20% of tuberculous pleuritis cases

- Tuberculin Skin Test (see Tuberculin Skin Test): negative in 33% of tuberculous pleuritis cases (when first evaluated)

- Probably due to sequestration of circulating purified protein derivative-reactive lymphocytes in the pleural space or the presence of suppressor cells (adherent monocytes or Fc-bearing lymphocytes) found in the blood but not in the pleural space

- Blind Pleural Biopsy (Abrams Needle): may be used in some cases -> demonstrates granulomas

- Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy (VATS) with Pleural Biopsy (see Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy): gold standard for diagnosis -> demonstrates granulomas

- Over 95% of granulomatous pleuritis is due to tuberculous pleuritis (granulomatous pleuritis can also be found in RA, fungal disease, sarcoidosis)

- Pleural Fluid Characteristics

- Clinical: exudative pleural effusion usually occurs 3-6 mo after infection (but may occur up to 1 yr later)

- Acute Illness (66% of Cases): mimics a bacterial pneumonia with associated parapneumonic pleural effusion

- Chest Pain (see Chest Pain)

- Cough (see Cough)

- Chronic Illness Presentation (33% of Cases)

- Low-Grade Fever (see Fever)

- Generalized Weakness (see Generalized Weakness)

- Weight Loss (see Weight Loss)

- Acute Illness (66% of Cases): mimics a bacterial pneumonia with associated parapneumonic pleural effusion

- Prognosis

- Most Cases of Tuberculous Pleuritis Resolve Spontaneously: however, without treatment, 50% progress to develop active tuberculosis within 5 yrs

Pleuritic Chest Pain (see Chest Pain)

- Epidemiology

- Occurs in 25% of Cases

Pulmonary Infiltrates (Pneumonia-Like Presentation)

- Pulmonary Infiltrates Occur in Approximately 30% of Primary Tuberculosis Cases

- Approximately 43% of Primary Tuberculosis Cases with Pulmonary Infiltrates Also Have an Associated Pleural Effusion

- Pattern of Pulmonary Infiltrates

- Perihilar/Right-Sided Pulmonary Infiltrates (Usually Middle-Lower Lung Zones) with Ipsilateral Hilar Lymphadenopathy: most common pattern

- Bilateral Pulmonary Infiltrates: present in only 2% of cases

- Contralateral Hilar Lymphadenopathy: may be seen in some cases

- Cavitation May Occur

- Time Course of Pulmonary Infiltrates: usually resolve slowly over months-years

- Approximately 15% of Cases Have Progression in Pulmonary Infiltrates After Skin Test Conversion (Consistent with Progressive Primary Tuberculosis)

Right Middle Lobe (RML) Atelectasis (see Atelectasis): may occur in association with hilar lymphadenopathy

- Physiology: multiple factors predispose to compromise of the right middle lobe bronchus

- Right Middle Lobe Bronchus is More Densely Surrounded by Lymph Nodes

- Right Middle Lobe Bronchus is Longer and Narrower (Often with a Fish Mouth Configuration)

- Right Middle Lobe Bronchus Has a Sharper Branching Angle

Other Manifestations

- Arthralgias (see Arthralgias)

- Fatigue (see Fatigue)

- Fever (see Fever)

- Usually gradual and low-grade

- May Be as High as 39 Degrees C in Some Cases

- Average Length of Fever Duration: 14-21 days

- Fever Resolves in 98% of Cases by 10 wks

Clinical Manifestations-Reactivation Tuberculosis

General Comments

- Definition of Reactivation Tuberculosis: reactivation of a primary tuberculosis focus that was seeded at the time of the primary infection

- Reactivation Tuberculosis Accounts for 90% of Adult Tuberculosis Cases in Non-HIV-Infected Patients

- Time Course: reactivation tuberculosis may remain undiagnosed (and potentially infectious) for years with the development of symptoms only late in the course of the disease

- Many of the Series of Reactivation Tuberculosis Cases in the Literature Report that Symptoms Begin Gradually and May Be Present for Weeks-Months Prior to Diagnosis

Dermatologic Manifestations

- Erythema Multiforme (see Erythema Multiforme)

- Night Sweats (see Night Sweats)

Hematologic Manifestations

Increased Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (see Deep Venous Thrombosis and Acute Pulmonary Embolism)

- Epidemiology: active tuberculosis has been reported to increase the rate of thromboembolism to 2%, comparable to the rate observed in patients with malignancy (Clin Infect Dis, 2014) [MEDLINE]

Infectious Manifestations

Sepsis (see Sepsis)

- Epidemiology

- Comparison of Septic Shock Due to Tuberculosis, as Compared to Other Etiologies of Septic Shock (Chest, 2013) [MEDLINE]

- Patients with Tuberculous Septic Shock Had Lower Body Mass Index (BMI) (BMI 22 vs BMI 27)

- Patients with Tuberculous Septic Shock Had Lower WBC Count (WBC 10.4 vs WBC 16.2)

- Patients with Tuberculous Septic Shock Had Higher Rate of HIV Infection (15% HIV-Positive vs 3% HIV-Positive)

- Comparison of Septic Shock Due to Tuberculosis, as Compared to Other Etiologies of Septic Shock (Chest, 2013) [MEDLINE]

- Clinical

- Extrapulmonary Disease is Present in >50% of Cases

- Prognosis

- High mortality rate

Otolaryngologic Manifestations

Laryngeal Tuberculosis

- Epidemiology

- Historically was associated with high mortality rate (due to occurrence late in the course of disease)

- Currently, Laryngeal Tuberculosis is Rare: occurs in <1% of tuberculosis cases

- Clinical

- Cough (see Cough)

- Dysphagia (see Dysphagia)

- Dysphonia (see Dysphonia)

- Hemoptysis (see Hemoptysis)

- Odynophagia (see Odynophagia)

- Stridor (see Stridor)

- Upper Airway Obstruction (see Obstructive Lung Disease): unlikely to produce significant upper airway obstruction

Pulmonary Manifestations

General Comments

- Pulmonary Involvement in Tuberculosis: the lung is the primary site of tuberculosis infection in 85% of HIV-negative patients

- Extrapulmonary TB is More Common in HIV

Bronchiectasis (see Bronchiectasis)

- Epidemiology

- May occur following primary tuberculosis or reactivation tuberculosis

- Diagnosis

- Bronchiectasis due to tuberculosis is most common in sites of reactivation tuberculosis (apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes), but may be found elsewhere, as well

- Clinical

- Hemoptysis (see Hemoptysis)

Endobronchial Tuberculosis

- Epidemiology

- Endobronchial Tuberculosis was Common in the Era Prior to the Use of Anti-Tuberculous Therapy

- Physiology

- Direct Extension to Bronchi from an Adjacent Parenchymal Focus (Usually a Cavity)

- Spread to Bronchi Via Infected Sputum

- Diagnostic

- Bronchoscopy

- Location of Endobronchial Lesions: more common in the mainstem and upper lobe bronchi (5% of cases involve the lower trachea)

- Appearance of Endobronchial Lesions: endobronchial gelatinous granulation tissue (mucosa may be nodular, red, or ulcerated, mimicking the appearance of a neoplasm)

- Endobronchial Biopsy/Brushing: usually diagnostic

- Bronchoscopy

- Clinical

- Barking Coughwith Sputum Production (see Cough): barking cough is present in 66% of cases

- Bronchial Stenosis (see Bronchial Stenosis)

- Bronchiectasis (see Bronchiectasis)

- Bronchorrhea (see Bronchorrhea): rarely occurs

- Broncholith (see Broncholithiasis): calcified lymph node (usually from tuberculosis) which erodes into the airway, causing airway obstruction or may be expectorated (lithoptysis)

- Hemoptysis (see Hemoptysis)

- Symptoms of Airway Obstruction

- Atelectasis (see Atelectasis)

- Dyspnea (see Dyspnea)

- Post-Obstructive Pneumonia

- Wheezing (see Obstructive Lung Disease)

- Tracheal Stenosis (see Tracheal Stenosis)

Extensive Pulmonary Destruction

- Epidemiology: rare

- Usually Associated with Untreated or Inadequately Treated Reactivation Tuberculosis

- May Occur in Primary Tuberculosis in Cases with Lymph Node Obstruction of Bronchi with Distal Atelectasis

- Diagnosis

- Large cavities or fibrosis of lung

- Clinical

- Progressive, extensive parenchymal destruction of areas in one or both lungs

Exudative Pleural Effusion (Tuberculous Pleuritis) (see Pleural Effusion-Exudate)

- Epidemiology

- In Many Parts of the World, Tuberculosis is the Most Common Etiology of Exudative Pleural Effusion

- However, in the US, Only 7549 Cases of Tuberculous Pleuritis Were Reported Between 1993-2003 (Accounting for Only 3.6% of the Total Tuberculosis Cases Seen in This Period)

- Tuberculous Pleuritis Can Occur as a Manifestation of Primary Tuberculosis or as a Manifestation of Reactivation Tuberculosis

- Tuberculous Pleuritis Due to Primary Tuberculosis: pleural effusion occurs in 33% of primary tuberculosis cases

- Tuberculous Pleuritis Due to Reactivation Tuberculosis

- Controversial Whether HIV Increases the Incidence of Tuberculous Pleuritis: studies conflict (however, the incidence of tuberculous pleuritis is higher in HIV patients with CD4 >200/μL than in those with CD <200/μL, consistent with its purported hypersensitivity-related mechanism)

- Analysis of TB Surveillance Data from 1993-2003 (Chest, 2007) [MEDLINE]

- Annual Proportion of Pleural Tuberculosis Cases Remained Constant (Pleural Tuberculosis Accounted for 3.6% of All Tuberculosis Cases)

- Pleural Tuberculosis Occurred Significantly More Often than Pulmonary Tuberculosis Among Persons ≥65 y/o

- Pleural Tuberculosis Occurred Significantly Less Often than Pulmonary Tuberculosis Among Children <15 y/o and Adults 45-64 y/o

- Drug-Resistance Patterns of Pleural Tuberculosis Broadly Reflected Those of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: however, isolates from pleural tuberculosis patients were less often resistant to at least isoniazid (6.0% vs 7.8%) and to at least one first-line tuberculosis drug (9.9% vs 11.9%), as compared with pulmonary TB patients

- In Many Parts of the World, Tuberculosis is the Most Common Etiology of Exudative Pleural Effusion

- Physiology

- Delayed hypersensitivity reaction

- Diagnosis

- Pleural Fluid Characteristics

- Straw-Colored Appearance: usually

- Lymphocytic Cell Differential: usually

- Approximately 11% are Neutrophil-Predominant (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]: neutrophilic predominance is more common early in the course of disease, in the first 2 wks

- Occasional Pleural Eosinophils: although eosinophils >10% (in the absence of pneumothorax or prior thoracentesis) excludes the diagnosis of tuberculous pleuritis

- Low Numbers of Mesothelial Cells

- Normal-Decreased Pleural Fluid Glucose

- Elevated Total Pleural Fluid Protein: total protein >5.0 g/d/L is suggestive of tuberculous pleuritis

- Elevated Pleural Fluid Adenosine Deaminase (ADA) (“Large Form” is Released from T-Cells)): may be useful (>70 U/L suggests tuberculous pleuritis, while level <40 U/L usually rules out tuberculous pleuritis)

- Approximately 7% of Cases Have a Normal Pleural ADA Level (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Elevated Adenosine Deaminase is Also Seen in Many Empyemas, Some Malignancies, and Most Sases of RA (All of These Have “Small Form” >> “Large Form” of the Enzyme)

- Elevated Pleural Fluid Interferon-γ: may be useful (always >2.3 U/mL (mean is 91.2 U/mL), as compared to levels <2.0 U/mL in other diagnoses)

- Pleural Fluid PCR for Mycobacterial DNA: may be positive

- Induced Sputum Culture: positive in 50% of cases (reflecting the microscopic foci of pulmonary infection which likely accompany many tuberculous pleural effusions)

- Chest CT

- Usually Unilateral

- Approximately 9-10% of Cases are Bilateral (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Usually Small-Moderate in Size

- Approximately 8% of Cases Have an Opacified Hemithorax (Eur J Intern Med, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Approximately 86% of Cases Have Coexistent Parenchymal Infiltrates, with the Pleural Effusion Usually on the Same Side as the Infiltrate (Chest, 2006) [MEDLINE]

- Even in the Absence of Overt Parenchymal Disease, There is Likely Microscopic Lung Involvement (Induced Sputum Cultures are Positive in the Same Percentage of Cases with/without a Parenchymal Infiltrate)

- Usually Unilateral

- Pleural Fluid Culture: positive in only 20% of tuberculous pleuritis cases

- Tuberculin Skin Test (see Tuberculin Skin Test): negative in 33% of tuberculous pleuritis cases (when first evaluated)

- Probably due to sequestration of circulating purified protein derivative-reactive lymphocytes in the pleural space or the presence of suppressor cells (adherent monocytes or Fc-bearing lymphocytes) found in the blood but not in the pleural space

- Blind Pleural Biopsy (Abrams Needle): may be used in some cases -> demonstrates granulomas

- Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy (VATS) with Pleural Biopsy (see Video-Assisted Thoracoscopy): gold standard for diagnosis -> demonstrates granulomas

- Over 95% of granulomatous pleuritis is due to tuberculous pleuritis (granulomatous pleuritis can also be found in RA, fungal disease, sarcoidosis)

- Pleural Fluid Characteristics

- Clinical: exudative pleural effusion usually occurs 3-6 mo after infection (but may occur up to 1 yr later)

- Acute Illness (66% of Cases): mimics a bacterial pneumonia with associated parapneumonic pleural effusion

- Chest Pain (see Chest Pain)

- Cough (see Cough)

- Chronic Illness Presentation (33% of Cases)

- Low-Grade Fever (see Fever)

- Generalized Weakness (see Generalized Weakness)

- Weight Loss (see Weight Loss)

- Acute Illness (66% of Cases): mimics a bacterial pneumonia with associated parapneumonic pleural effusion

- Prognosis

- Most Cases of Tuberculous Pleuritis Resolve Spontaneously: however, without treatment, 50% progress to develop active tuberculosis within 5 yrs

Increased Risk of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis (see Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis)

- Epidemiology: can occur following pulmonary tuberculosis with cavitary disease

Increased Risk of Lung Cancer (see Lung Cancer)

- Epidemiology

- Systematic Reviews Examining the Relationship Between Tuberculosis and Lung Cancer (Int J Cancer, 2009) [MEDLINE]

- Tuberculosis was Associated with an Increased Risk of Lung Cancer (Especially Adenocarcinoma)

- Taiwan National Health Insurance Database Study of Relationship Between Tuberculosis and Lung Cancer (Cancer, 2011) [MEDLINE]

- Tuberculosis was Associated with an Increased Risk of Lung Cancer

- Systematic Reviews Examining the Relationship Between Tuberculosis and Lung Cancer (Int J Cancer, 2009) [MEDLINE]

- Physiology: mycobacterial cell wall components can induce nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species production (these agents have been implicated in DNA damage)

Isolated Hilar/Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy (see Mediastinal Mass)

- Clinical

- May Be Asymptomatic

- Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy May Result in Extrinsic Airway Compression (Especially in Children)

Pneumothorax (see Pneumothorax)

- Epidemiology: historically more prevalent in the era prior to the advent of anti-tuberculous therapy

- Currently, Pneumothorax Due to Tuberculosis is Rare

- Clinical

- Bronchopleural Fistula (BPF) (see Bronchopleural Fistula): may occur

Pulmonary Infiltrates/Pneumonia

- Epidemiology

- Impact of Age on the Incidence and Outcome of Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- In Non-Endemic Countries, the Incidence of Pulmonary Tuberculosis is 2-3x Higher in Older Adults (Especially in Institutionalized) and the Risk of Death is Higher*

- Impact of Comorbid Conditions on the Severity and Outcome of Tuberculosis

- Presence of Comorbid Conditions (Such as Diabetes Mellitus, HIV Infection, and Anti-TNFα Therapy) Increase the Incidence of Smear Positivity, Cavitation, Treatment Failure, and Non-Tuberculosis-Related Death (Epidemiol Infect, 2015) [MEDLINE]

- Impact of Age on the Incidence and Outcome of Pulmonary Tuberculosis

- Diagnosis

- Location: infiltrates are most commonly in the upper lobe (apical-posterior > anterior segment) or superior segment of the lower lobe

- May Be Due to Relatively Poor Lymphatic Flow in the Upper Lobes with Poor Organism Clearance or to the Preference of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis for High Oxygen Tension in the Apical Areas of the Lung (Although Mycobacterium Tuberculosis May Not Be an Obligate Aerobe)*

- Simon Focus: small original site of infection which appears as small scar

- Lower Lobe-Predominant Disease: may occur with older age, HIV infection, chronic kidney disease, liver disease, silicosis, or corticosteroid therapy

- Cavitation: may occur

- Chest X-Ray (CXR) (see Chest X-Ray): normal in 5% of cases

- High-Resolution Chest CT (HRCT) (see High-Resolution Chest Computed Tomography)

- Imaging Technique of Choice to Identify Early Bronchogenic Spread of Tuberculosis

- Centrilobular 2-4 mm Nodules or Branching Linear Lesions (Indicative of Intrabronchiolar or Peribronchiolar Caseating Necrosis): most common finding

- Sputum Acid-Fast Bacteria (AFB) Smear/Culture (see Sputum Culture)

- Sputum AFB Smear/Culture is More Commonly Positive in Immunocompromised Patients -About 100 organisms per mL of sputum are required to be AFB culture-positive

- Approximately 20-50% of Active Tuberculosis Cases Have 3 Negative AFB Smears

- About 6000-10,000 organisms/mL of sputum are required to visualize only 2-3 organisms on the smear

- Location: infiltrates are most commonly in the upper lobe (apical-posterior > anterior segment) or superior segment of the lower lobe

- Clinical

- Chest Pain (see Chest Pain)

- May Be Pleuritic in Cases Where the Infiltrate Abuts the Pleura (With or Without a Pleural Effusion)

- Cough with Sputum Production (see Cough)

- Yellow-Green or Blood-Streaked Sputum

- Rarely Foul-Smelling

- Dyspnea (see Dyspnea)

- May Occur in Cases with Extensive Parenchymal Disease, Pneumothorax, Pleural Effusion, etc

- Hemoptysis (see Hemoptysis)

- Occurs in 25% of Cases

- May Be Massive in Some Cases

- Chest Pain (see Chest Pain)

Pulmonary Gangrene (see Necrotizing Pneumonia and Pulmonary Gangrene)

- Epidemiology

- May occur in some cases

- Prognosis

- High Mortality

Rasmussen’s Aneurysm

- Epidemiology

- Uncommon

- Physiology: formation of aneurysm within a cavity from a prior infection, with rupture of aneurysm in the cavity

- Diagnosis

- Massive Hemoptysis (see Hemoptysis)

Tuberculoma (see Lung Nodule or Mass)

- Physiology

- May Represent Primary Tuberculosis or an Encapsulated Focus of Reactivation

- Diagnosis

- Chest CT (see Chest Computed Tomography)

- Upper Lobe-Predominant Lung Nodule/Mass: R>L

- May Be Lobulated

- May Calcify

- Rarely Cavitates

- Chest CT (see Chest Computed Tomography)

Tuberculous Empyema

- Diagnosis

- Thoracentesis (see Thoracentesis)

Upper Lobe Fibrocalcific Pulmonary Infiltrates (see xxxx)

- Epidemiology: occurs in 5% of cases

- Physiology: believed to be indicative of healed primary tuberculosis -> however, active tuberculosis should be ruled out in cases where stability of such radiographic changes cannot be confirmed or if patient has pulmonary symptoms

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Anorexia (see Anorexia)

- xxx

Painful Ulcers of Mouth/Tongue/Larynx/Gastrointestinal Tract (see xxxx)

- Epidemiology

- May Occur in the Absence of Anti-Tuberculous Therapy

- Physiology

- Due to chronic expectoration and swallowing of highly infectious sputum

Weight Loss (see Weight Loss)

- Epidemiology

- XXX

Neurologic Manifestations

- Fatigue (see Fatigue)

Renal Manifestations

- Acute Interstitial Nephritis (see Acute Interstitial Nephritis)

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion (SIADH) (see Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion)

Rheumatologic Manifestations

- Clubbing (see xxxx)

Other Manifestations

- Fever (see Fever)

- Usually Low-Grade, But May Be More Significant with Progression of Disease

- Classical Pattern: diurnal (peaking in late afternoon or early evening)

- Malaise

- Wasting (“Consumption”)

Tuberculosis in Pregnancy (see Pregnancy)

- Tuberculosis in Pregnancy is Associated with Lower Infant Birth Weight and, in Rare Cases, Fetal Acquisition of Tuberculosis: for these reasons, untreated tuberculosis represents a greater hazard to a pregnant woman and her fetus than does tuberculosis treatment

- Treatment of Tuberculosis in a Pregnant Woman Should Be Initiated Whenever the Probability of Tuberculosis is Moderate-High: see treatment below

Tuberculosis Associated with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- xxx

Clinical Manifestations-Miliary (Disseminated) Tuberculosis

Epidemiology

- History

- Term was first used in 1700 by John Jacobus Manget to describe the appearance of the lung (surface covered with small, firm white nodules, which looked like millet seeds)

- The Term Miliary Tuberculosis is Currently Used to Describe All Types of Disseminated Hematogenously-Spread Tuberculosis

- Miliary Tuberculosis Can Occur Following Primary Tuberculosis or Via Reactivation Tuberculosis with Subsequent Dissemination

- Risk Factors

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus): risk increases with decreasing CD4 count

- Approximately 70% of HIV-Associated Tuberculosis Cases with CD4 <100 Have Extrapulmonary Involvement

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus): risk increases with decreasing CD4 count

Physiology

- Tuberculosis Due to Hematogenous Dissemination

Diagnosis

Frequency of Positive Acid-Fast Bacteria (AFB) Smear/Culture in Miliary Tuberculosis (Am J Med, 1990) [MEDLINE]

- General Comments

- Multiple Sites Should Be Sampled: probability of positive smears increases with the number of sites sampled

- Sputum

- Smear: 33% positive

- Culture: 62% positive

- Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

- Smear: 27% positive

- Culture: 55% positive

- Gastric Aspirate

- Smear: 43% positive

- Culture: 100% positive

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

- Smear: 8% positive

- Culture: 60% positive

- Urine

- Smear: 14% positive

- Culture: 33% positive

- Serosal (Ascites, Pleural, Pericardial)

- Smear: 6% positive

- Culture: 44% positive

Clinical

General Comments

- Clinical Presentation is Variable: presentation is more likely to be subacute/chronic than acute

- Median Duration of Illness: usually months

Breast Manifestations

- General Comments

- Breast Involvement in Miliary Tuberculosis is Rare

- Breast Mass (see Breast Mass)

Cardiovascular Manifestations

- Mycotic Aortic Aneurysm (see Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm)

- Physiology: spread from lymph node or vertebral osteomyelitis to aorta with subsequent hematogenous dissemination or hematogenous spread to the aortic wall vasa vasorum

- Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm (see Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm)

- Epidemiology: rare

- Tuberculous Endocarditis (see Endocarditis)

- Epidemiology: rare

- Tuberculous Myocarditis (see Myocarditis)

- Epidemiology: uncommon

- Tuberculous Pericarditis (see Acute Pericarditis)

- Epidemiology: usually occurs late in the disease course

- Clinical

- Pericardial Effusion (see Pericardial Effusion)

Dermatologic Manifestations

- General Comments

- Skin Involvement in Miliary Tuberculosis is Rare

- HIV Infection Increases the Incidence of Skin Manifestations in Miliary Tuberculosis

- Night Sweats (see Night Sweats: common

- Tuberculous Cutis Miliaris Disseminata

- Maculopapular rash

Endocrine Manifestations

- Adrenal Insufficiency (see Adrenal Insufficiency)

- Epidemiology: although adrenal involvement is found in 40% of autopsy cases, clinical adrenal insufficiency is present in only 1% of miliary tuberculosis cases

- Thyroid Gland Involvement

- Epidemiology: case reports

- Clinical

- Hyperthyroidism (see Hyperthyroidism)

- Hypothyroidism (see Hypothyroidism)

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

- Tuberculous Cholecystitis (see Acute Cholecystitis)

- Tuberculous Enteritis

- Clinical

- Non-Specific Symptoms

- Clinical

- Tuberculous Hepatitis

- Epidemiology

- Liver is frequently involved in miliary tuberculosis

- Diagnosis

- Liver Biopsy (see Liver Biopsy): granulomas may be found in in 91-100% of miliary tuberculosis cases -> liver biopsy is believed to have the highest yield in miliary tuberculosis

- Clinical

- Abnormal Liver Function Tests (LFT’s) with Cholestatic Jaundice

- Elevated Alkaline Phosphatase

- Hyperbilirubinemia

- Transaminitis

- Diarrhea (see Diarrhea)

- Fulminant Hepatic Failure (see Fulminant Hepatic Failure): rare

- Nausea/Vomiting (see Nausea and Vomiting)

- Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) Abdominal Pain (see Abdominal Pain)

- Abnormal Liver Function Tests (LFT’s) with Cholestatic Jaundice

- Epidemiology

- Tuberculous Pancreatitis (see Acute Pancreatitis)

- Tuberculous Peritonitis (see Peritonitis)

- Physiology: spread from adjacent organs

- Diagnosis

- Laparoscopy (see Laparoscopy): miliary lesions on peritoneal surface (with biopsy positive for caseating granulomas with/without AFB)

- Paracentesis (see Paracentesis): elevated total protein, lymphocytosis

- Clinical

- Ascites (see Ascites)

Hematologic Manifestations

- General Comments

- Diagnosis

- Bone Marrow Biopsy (see Bone Marrow Biopsy): granulomas are demonstrated in 31-82% of miliary tuberculosis cases

- Diagnosis

- Anemia (see Anemia)

- Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (see Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis)

- Epidemiology: reported in association with disseminated tuberculosis (NEJM, 2020) [MEDLINE]

- Leukocytosis (see Leukocytosis)

- Leukopenia (see Leukopenia)

- Thrombocytopenia (see Thrombocytopenia)

- Thrombocytosis (see Thrombocytosis)

Infectious Manifestations

- Fever (see Fever): common

- Sepsis (see Sepsis)

- Epidemiology

- Cases Have Been Reported (Crit Care Med, 1992) [MEDLINE]

- Epidemiology

Neurologic Manifestations

- Tuberculous Meningitis

- Diagnosis

- Brain MRI (see Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging): leptomeningeal enhancement, basal cistern enhancement, hydrocephalus, parenchymal lesions

- Head CT (see Head Computed Tomography)

- Lumbar Puncture (see Lumbar Puncture)

- Elevated CSF Pressure

- WBC: usually <300 (usually with lymphocytosis, although neutrophils may be seen early in the course of disease)

- Total Protein: elevated (usually > 80 mg/dL)

- Glucose: decreased (but not <45 mg/dL)

- AFB Smear: positive in only 8% of cases (Am J Med, 1990) [MEDLINE]

- AFB Culture: positive in 60% of cases (Am J Med, 1990) [MEDLINE]

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis PCR: although not FDA-approved for this indication, it is often used

- Clinical

- Diagnosis

- Tuberculoma

Ophthalmologic Manifestations

- Choroidal Tubercles

- Characteristic of miliary tuberculosis

Otolaryngologic Manifestations

- Laryngitis (see Laryngitis)

- Otitis Media (see Otitis Media)

- Epidemiology: case reports

Pulmonary Manifestations

- General Comments

- Pulmonary Disease is Present in >50% of Miliary Tuberculosis Cases

- Diagnosis

- Chest X-Ray

- Normal: 50% of cases

- Diffuse Reticulonodular/Miliary Infiltrate (see Interstitial Lung Disease)

- Most Common Pulmonary Radiographic Pattern

- May Only Be Observed in Some Cases Days-Weeks After Initial Presentation

- Alveolar Infiltrates: may occur

- Cavities: may occur

- Hilar/Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy (see Mediastinal Mass)

- High-Resolution Chest CT (HRCT) (see High-Resolution Chest Computed Tomography): more sensitive than CXR for miliary tuberculosis

- Multiple 2-3 mm Nodules: however, this is not specific for miliary tuberculosis, as disseminated nodules can also be seen in other diseases (Haemophilus Influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Candida Albicans, Sarcoidosis, Metastatic Adenocarcinoma, Lymphoma, Amyloidosis, Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis, and Pneumoconiosis)

- Interlobular Septal Thickening

- Sputum Smear/Culture (see Sputum Culture)

- Bronchoscopy with Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) (se Bronchoscopy)

- Transbronchial Biopsy: granulomas may be demonstrated in 60-70% of miliary tuberculosis cases

- Open Lung Biopsy (see Open Lung Biopsy): may be diagnostic

- Chest X-Ray

- Clinical

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) (see Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome)

- Cough (see Cough)

- Dyspnea (see Dyspnea)

- Hypoxemia (see Hypoxemia)

- Pleural Effusion (see Pleural Effusion-Exudate)

- Pleuritic Chest Pain (see Chest Pain)

Renal Manifestations

- Flank Pain (see Flank Pain)

- Cystitis

- Epididymitis (see Epididymitis)

- Female Genital Tract Involvement

- Menstrual Irregularities

- Hematuria (see Hematuria)

- Diagnosis

- AFB Stain: may yield false-positive, due to the presence of nonpathogenic, nontuberculous mycobacteria in many patients

- Diagnosis

- Hydronephrosis

- Hypercalcemia (see Hypercalcemia)

- Epidemiology: may occur rarely in miliary tuberculosis

- Prostatitis (see Prostatitis)

- Proteinuria (see Proteinuria)

- Sterile Pyuria (see Pyuria)

- Epidemiology: found in 30% of cases (with negative mycobacterial cultures)

- Urine Cultures May Be Positive in Some Cases in the Absence of an Active Urinary Sediment

- Epidemiology: found in 30% of cases (with negative mycobacterial cultures)

- Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion (SIADH)

- Epidemiology

- Hyponatremia is most common electrolyte abnormality in miliary tuberculosis

- Clinical

- Hyponatremia (see Hyponatremia)

- Epidemiology

Rheumatologic/Orthopedic Manifestations

- Diagnosis

- CT/MRI Imaging

- Useful to define lesions

- Fine Needle Aspiration/Biopsy

- CT/MRI Imaging

- Clinical

- Pott’s Disease (Spinal Tuberculosis): accounts for 50-70% of spinal tuberculosis cases

- Back Pain with Spinal Tenderness

- Most Commonly Involves the Lower Thoracic and Lumbar Vertebrae (Most Commonly Involves the Upper Thoracic Vertebrae in Children): may involve multiple vertebrae

- Intervertebral Disk Destruction is Highly Suggestive of Spinal Tuberculosis

- May Extend Contiguously to Form Soft Tissue Abscess (“Cold Abscess”)

- Tuberculous Arthritis (see xxxx)

- Pott’s Disease (Spinal Tuberculosis): accounts for 50-70% of spinal tuberculosis cases

Tuberculous Lymphadenitis

- Diagnosis

- Cervical Lymph Node Biopsy

- Clinical

- Scrofula (Cervical Lymphadenopathy with Lymphadenitis) (see Lymphadenopathy)

- More Common in Asian Pacific Islanders

- Scrofula (Cervical Lymphadenopathy with Lymphadenitis) (see Lymphadenopathy)

Prevention

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Vaccination (see Bacillus Calmette-Guerin)

- BCG is a WHO-Recommended Vaccination During Infancy in Endemic TB Regions of the World: however, BCG is generally not recommended in the US

- BCG is Used to Protect Infants/Young Children from Serious, Life-Threatening Miliary TB and Tuberculous Meningitis

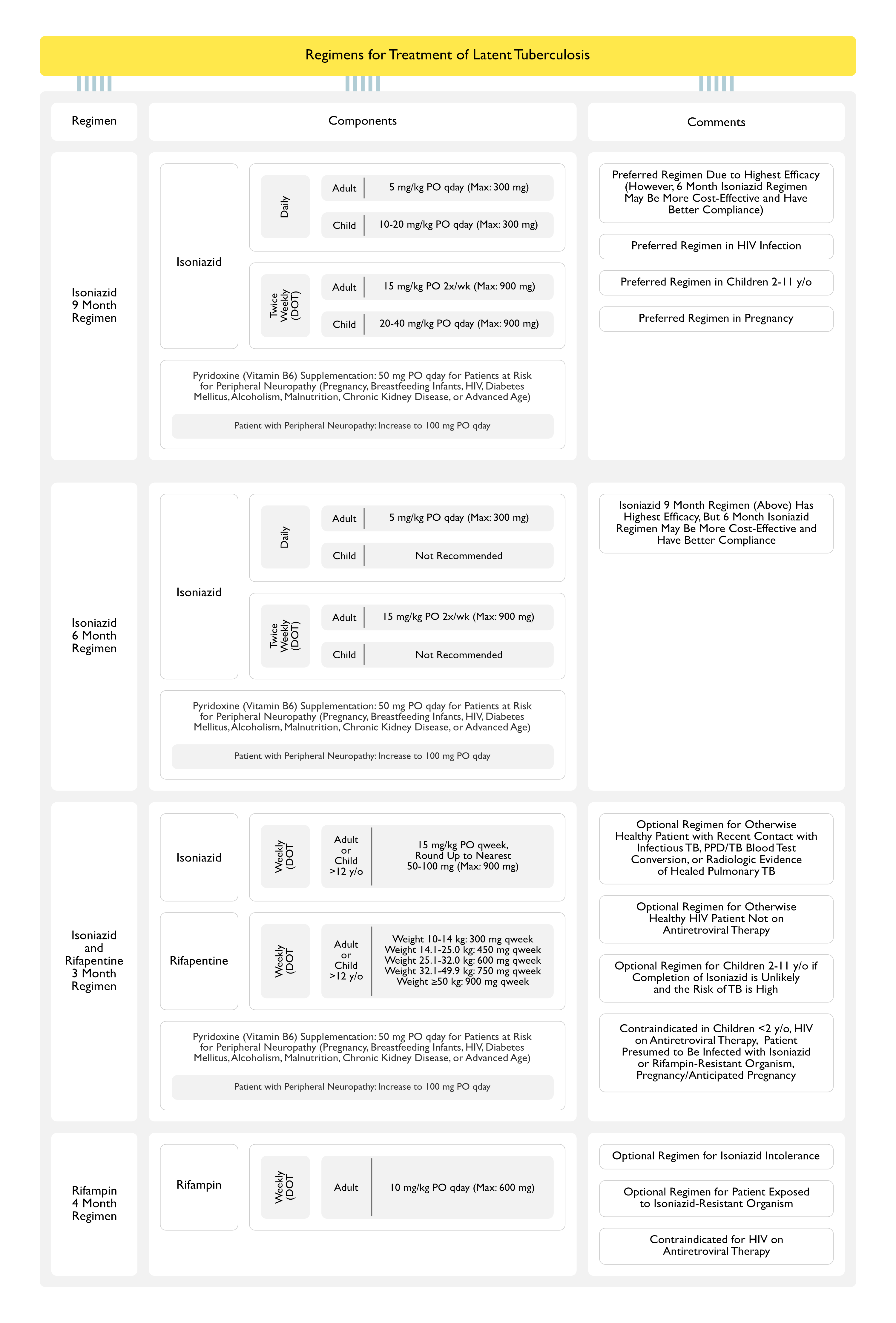

Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis (Per CDC Recommendations, Accessed 9/16) [LINK]

General Comments

- Obtain Chest X-Ray (CXR) Prior to Treatment to Rule Out Active Tuberculosis

- Choose Regimen for Latent Tuberculosis Based on the Following Features

- Coexisting Medical Illness

- Drug Susceptibility of Presumed Source Case

- Potential for Drug Interactions

- Fluoroquinolones are Not Effective in Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis (see Fluoroquinolones)

- Patients at High Risk for TB Disease and Suspected Poor Compliance: directly-observed therapy (DOT) should be used for the treatment of latent tuberculosis

- Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis in Pregnancy (see Pregnancy): recommended to wait until after delivery, since pregnancy does not increase the risk of progression to disease and isoniazid hepatotoxicity may occur during pregnancy and post-partum period

Regimens

Isoniazid (INH) 9 Month Regimen (see Isoniazid)

- Indications

- 9 Month Daily Isoniazid Regimen is Preferred, Due to Highest Efficacy: however, the 6 month isoniazid regimen may be more cost-effective and have better patient compliance

- 9 Month Daily Isoniazid Regimen is Preferred in Patients with HIV Infection

- 9 Month Daily Isoniazid Regimen is Preferred in Children 2-11 y/o

- 9 Month Daily Isoniazid Regimen is Also the Preferred Regimen in Pregnancy

- Daily

- Adult: 5 mg/kg (Max: 300 mg) PO qday

- Children: 10-20 mg/kg (Max: 300 mg) PO qday

- Twice Weekly Via Directly-Observed Therapy (DOT)

- Adult: 15 mg/kg (Max: 900 mg) PO 2x/week

- Children: 20-40 mg/kg (Max: 900 mg) PO 2x/week

- Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) Supplementation (see Vitamin B6): administer 50 mg qday to all patients with risk of neuropathy (pregnancy, breastfeeding infants, HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, malnutrition, chronic kidney disease, or advanced age)

- Pyridoxine 100 mg qday Should Be Used for Patients with Peripheral Neuropathy

Isoniazid (INH) 6 Month Regimen (see Isoniazid)

- Indications

- 9 Month Isoniazid Regimen (Above) is Preferred, as it is More Efficacious: however, the 6 month INH regimen may be more cost-effective and have better patient compliance

- Daily

- Adult: 5 mg/kg (Max: 300 mg) PO qday

- Children: not recommended

- Twice Weekly Via Directly-Observed Therapy (DOT): with pyridoxine supplementation (see Vitamin B6)

- Adult: 15 mg/kg (Max: 900 mg) PO 2x/week

- Children: not recommended

- Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) Supplementation (see Vitamin B6): administer 50 mg qday to all patients with risk of neuropathy (pregnancy, breastfeeding infants, HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, malnutrition, chronic kidney disease, or advanced age)

- Pyridoxine 100 mg qday Should Be Used for Patients with Peripheral Neuropathy

Isoniazid (INH) + Rifapentine (RPT) 3 Month Regimen (see Isoniazid and Rifapentine)

- Indications

- Optional Regimen for Otherwise Healthy Patient with Recent Contact with Infectious TB, with PPD/TB Blood Test Conversion, or Radiologic Evidence of Healed Pulmonary TB

- Optional Regimen for Otherwise Healthy HIV Patient Not on Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Optional Regimen for Children 2-11 y/o if Completion of INH is Unlikely and the Risk of TB Disease is High

- Contraindications

- Children <2 y/o

- HIV Infection on Antiretroviral Therapy (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Patient Presumed to Be Infected with Isoniazid or Rifampin-Resistant Organism

- Pregnancy (or Anticipated Pregnancy While Taking the Regimen) (see Pregnancy)

- Weekly Via Directly-Observed Therapy (DOT)

- Adult and Children >12 y/o

- Isoniazid: 15 mg/kg Rounded Up to the Nearest 50-100 mg (Max: 900 mg) PO qweek

- Rifapentine:

- Weight 10–14 kg: 300 mg PO qweek

- Weight 14.1–25.0 kg: 450 mg PO qweek

- Weight 25.1–32.0 kg: 600 mg PO qweek

- Weight 32.1–49.9 kg: 750 mg PO qweek

- Weight ≥50.0 kg: 900 mg PO qweek

- Adult and Children >12 y/o

- Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) Supplementation (see Vitamin B6): administer 50 mg qday to all patients with risk of neuropathy (pregnancy, breastfeeding infants, HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, malnutrition, chronic kidney disease, or advanced age)

- Pyridoxine 100 mg qday Should Be Used for Patients with Peripheral Neuropathy

Rifampin 4 Month Regimen (see Rifampin)

- Indications

- Optional Regimen for Patient Who is Intolerant of INH

- Optional Regimen for Patient Who Has Been Exposed to an INH-Resistant Organism

- Contraindications

- HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Daily

- Adult: 10 mg/kg (Max: 600 mg) PO qday

Monitoring

- Baseline and Periodic Liver Function Tests (LFT’s) are Recommended for Specific Patient Groups Only

- Alcoholic Abuse (see Ethanol)

- Chronic Liver Disease (see Cirrhosis)

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Pregnancy/Postpartum (see Pregnancy)

Clinical Efficacy

- Thibela Study Examining Mass Treatment with Isoniazid Preventive Therapy x 9 mo in South African Miners with Negative Screening (NEJM, 2014) [MEDLINE]

- *Mass Preventative Therapy with INH Did Not Decrease the Incidence or Prevalence of Tuberculosis

- INH Decreased the Incidence of Tuberculosis During Treatment, But There was a Subsequent Rapid Loss of Protection After Discontinuation

- Network Meta-Analysis Studying the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis (Ann Intern Med, 2014) [MEDLINE]

- Regimens Containing Rifamycins (Rifampin, etc) for >3 mo were Efficacious in Preventing TB, Potentially More So Than Isoniazid Alone

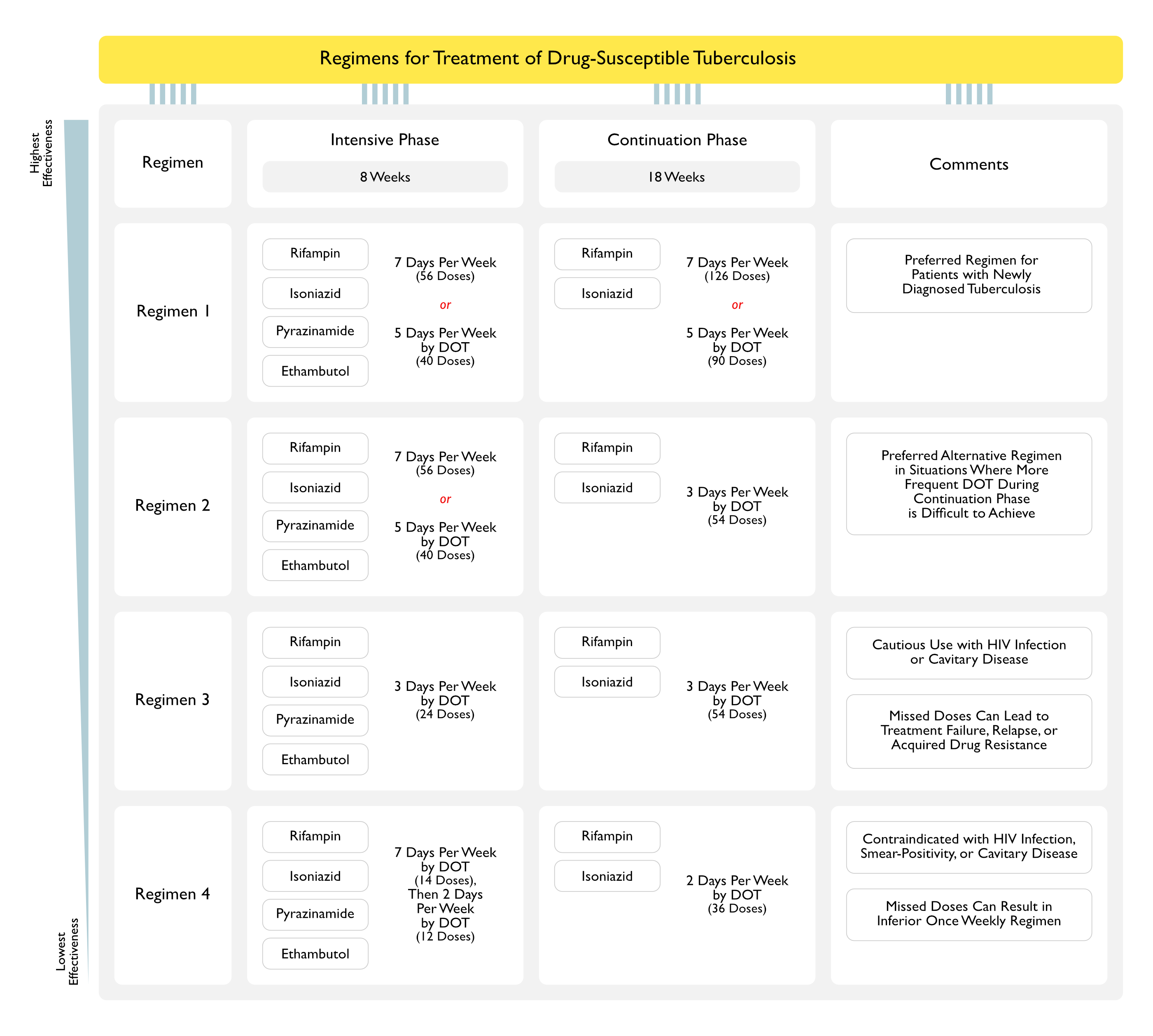

Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis (American Thoracic Society, ATS/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC/Infectious Diseases Society of America, IDSA 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines) (Clin Infect Dis, 2016) [MEDLINE]

General Comments

- There are 10 Medications Which are FDA-Approved to Treat Tuberculosis

- First-Line Medications

- Rifampin (see Rifampin)

- Isoniazid (INH) (see Isoniazid)

- Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) Supplementation (see Vitamin B6): administer 50 mg qday to all patients with risk of neuropathy (pregnancy, breastfeeding infants, HIV infection, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, malnutrition, chronic kidney disease, or advanced age)

- Pyridoxine 100 mg qday Should Be Used for Patients with Peripheral Neuropathy

- Pyrazinamide (PZA) (see Pyrazinamide)

- Ethambutol (see Ethambutol)

Indications for Directly-Observed Therapy (DOT)

- Children/Adolescents

- Correctional/Long-Term Care Facility Resident

- Current or Prior Substance Abuse

- Delayed Culture Conversion (Sputum Obtained At or After Completion of the Intensive Phase of Therapy Remains Positive)

- Drug Resistance

- History of Non-Adherence to Therapy

- HIV Infection (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Homelessness

- Mental/Emotional/Physical Disability (Cognitive Deficits/Dementia, Neurologic Deficits, Medically-Fragility, Blindness or Severe Loss of Vision, etc)

- Positive Sputum Smear

- Prior Treatment for Latent/Active Tuberculosis

- Relapse

- Treatment Failure

- Use of Intermittent Dosing

Indications for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

- Diabetes Mellitus (see Diabetes Mellitus)

- Drug Interactions

- HIV Infection (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Impaired Renal Clearance

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) (see Chronic Kidney Disease)

- Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT) (see Hemodialysis)

- Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) (see Peritoneal Dialysis)

- Poor Response to Treatment Despite Adherence and Fully Drug-Susceptible Organism

- Severe Gastrointestinal Abnormalities

- Chronic Diarrhea with Malabsorption (see xxxx)

- Severe Gastroparesis (see Gastroparesis)

- Short Bowel Syndrome (see Short Gut Syndrome)

- Treatment Using Second-Line Drugs

Management of Treatment Interruption

- General Comments: per expert opinion, patients who are lost to follow-up (while on treatment) and brought back to therapy, with interim treatment interruption, should have sputum resent for AFB smear, culture, and drug susceptibility testing

- Interruption During Intensive Phase

- Lapse <14 Days: continue treatment to complete planned total number of doses (as long as all doses are completed within 3 mo)

- Lapse ≥14 Days: restart treatment from the beginning

- Interruption During Continuation Phase

- Received ≥80% of Doses and Sputum was AFB Smear Negative on Initial Testing: further therapy may not be necessary

- Received ≥80% of Doses and Sputum was AFB Smear Positive on Initial Testing: continue therapy until all doses are completed

- Received <80% of Doses and Accumulative Lapse is <3 mo in Duration: continue therapy until all doses are completed (full course), unless consecutive lapse is >2 mo

- If treatment cannot be completed within recommended time frame for regimen, restart therapy from the beginning (ie, restart intensive phase, to be followed by continuation phase)

- The recommended time frame for regimen in tuberculosis control programs in the US and in several European countries is to administer all of the specified number of doses for the intensive phase within 3 mo and those for the 4 mo continuation phase within 6 mo, so that the 6 mo regimen is completed within 9 mo

- Received <80% of Doses and Lapse is ≥3 mo in Duration: restart therapy from the beginning, new intensive and continuation phases (ie, restart intensive phase, to be followed by continuation phase)

Preferred Regimen (Regimen 1) (Recommendation 3a, Strong Recommendation, Moderate Certainty in the Evidence)

- Intensive Phase (Daily for 8 Week Course): 56 Doses (7 Days Per Week) or 40 Doses (5 Days Per Week by DOT)

- Rifampin (see Rifampin): 10 mg/kg qday (usually 600 mg) in adults

- Isoniazid (INH) (see Isoniazid): 5 mg/kg qday (usually 300 mg) in adults

- Pyrazinamide (PZA) (see Pyrazinamide)

- Lean Body Weight 40-55 kg (adult): 1000 mg qday

- Lean Body Weight 56-75 kg (adult): 1500 mg qday

- Lean Body Weight 76-90 kg (adult): 2000 mg qday

- Ethambutol (see Ethambutol): ethambutol can be discontinued if drug susceptibility studies demonstrate susceptibility to first-line agents

- Lean Body Weight 40-55 kg (adult): 800 mg qday

- Lean Body Weight 56-75 kg (adult: 1200 mg qday

- Lean Body Weight 76-90 kg (adult): 1600 mg qday

- Continuation Phase (Daily for 18 Week Course): 126 Doses (7 Days Per Week) or 90 Doses (5 Days Per Week by DOT)

- General Comments: continuation phase should be extended to 7 mo in the following specific populations

- Patient with Cavitary Pulmonary Tuberculosis Caused by Drug-Susceptible Organisms and Whose Sputum Culture Obtained at the Completion of Intensive Treatment Phase (2 mo) Remains Positive

- Patient Whose Intensive Phase of Treatment Did Not Include PZA

- Patient Being Treated with Once Weekly INH and Rifapentine and Whose Sputum Culture Obtained at the Completion of Intensive Treatment Phase (2 mo) Remains Positive

- Rifampin (see Rifampin): 10 mg/kg qday (usually 600 mg) in adults

- Isoniazid (INH) (see Isoniazid): 5 mg/kg qday (usually 300 mg) in adults

- General Comments: continuation phase should be extended to 7 mo in the following specific populations

Monitoring

Rash

- All Anti-Tuberculous Drugs Can Cause a Rash

- Pruritic Rash without Mucous Membrane Involvement or Systemic Signs (Fever, etc): symptomatic treatment with antihistamines

- Petechial Rash (Suggestive of Thrombocytopenia from a Rifamycin Hypersensitivity)

- With Thrombocytopenia: discontinue rifamycin permanently and follow platelet count

- Generalized Erythematous Rash: discontinue anti-tuberculous drugs -> wait several days until rash is substantially better before serially restarting the individual drugs q2-3 days (in order: rifampin -> isoniazid -> ethambutol -> pyrazinamide)

- Presence of Fever and/or Mucous Membrane Involvement Suggests Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis, Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS), or Drug Hypersensitivity Syndrome

- Hypersensitivity Reactions to Multiple Anti-Tuberculous Drugs Can Particularly Occur in HIV Patients

- Systemic Corticosteroids May Be Used for Severe Systemic Reactions: this does not worsen outcomes

Hepatotoxicity (see Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity)

- Drug-Induced Hepatitis is the Most Serious Adverse Reaction to the First-Line Ani-Tuberculous Drugs

- Rifampin, Isoniazid, and Pyrazinamide Can All Cause Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity

- Elevated Alkaline Phosphatase/Hyperbilirubinemia May Be Seen with Rifampin Hepatotoxicity

- Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity is Characterized by ALT ≥3x the Upper Limit of Normal in the Presence of Hepatitis Symptoms or ≥5x the Upper Limit of Normal in the Absence of Hepatitis Symptoms

- ALT <5x the Upper Limit of Normal: mild hepatotoxicity

- ALT 5-10x the Upper Limit of Normal: moderate hepatotoxicity

- ALT >10 the Upper Limit of Normal (>500 IU): severe hepatotoxicity

- Asymptomatic Increase in ALT Occurs in 20% of Patients Treated with the Standard 4 Drug Regimen: in most patients, asymptomatic ALT elevations resolve spontaneously

- Once ALT Decreases to <2x the Upper Limit of Normal, Ant-Tuberculous Drugs Can Be Sequentially Restarted at 1 Week Intervals: in order, rifampin -> isoniazid -> pyrazinamide

- Baseline and Periodic Liver Function Tests (LFT’s) are Recommended for Specific Patient Groups Only

- Alcoholic Abuse (see Ethanol)

- Chronic Liver Disease (see Cirrhosis)

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (see Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

- Pregnancy/Postpartum (see Pregnancy)

Drug Fever

- Drug Fever is a Diagnosis of Exclusion

- Drug Fever Does Not Follow a Specific Pattern and Eosinophilia May Be Absent

- Patients with Drug Fever Generally Feel Well, Despite the Fever

- Discontinuing the Drugs Usually Leads to Resolution of the Fever Within 24 hrs

- Once Fever Has Resolved, Drugs Can Be Serially Restarted: as above

Optic Neuritis (see Optic Neuritis)

- Incidence of Ethambutol-Related Visual Impairment: 2.25% (22.5 cases per 1000 persons)

- If Vision Does Not Improve with Cessation of Ethambutol, Isoniazid Should Be Discontinued, as it it Also a Rare Cause of Optic Neuritis

Special Treatment Considerations

Tuberculous Pleuritis

- Time Course of Resolution with Treatment

- Patient Usually Becomes Afebrile Within 2 wks

- Pleural Effusion Usually Resolves Within 6 wks

- Pleural Effusion May Occasionally Worsen with Therapy or Develop During the Course of Treatment for Parenchymal Tuberculosis

- Mild Residual Pleural Fibrosis May Be Found a Year After Treatment in 50% of Cases

- Role of Adjunctive Corticosteroids (see Corticosteroids): controversial, but may be considered in patients with marked symptoms

- Corticosteroids Should Not Be Used in HIV-Associated Cases: due to the increased risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma

- Pleural Space Drainage: does not appear to impact outcome

Pott’s Disease

- May Additionally Require Orthopedic/Neurosurgical Consultation if Disease Progresses Despite Therapy or if There is Neurologic Deterioration

Tuberculous Pericarditis

- Adjunctive Corticosteroids are Not Routinely Recommended in the Treatment of Tuberculous Pericarditis (Recommendation 7, Conditional Recommendation, Very Low Certainty in the Evidence) (see Corticosteroids)

Tuberculous Meningitis

- Adjunctive Corticosteroids are Recommended in the Treatment of Tuberculous Meningitis (Recommendation 8, Strong Recommendation, Moderate Certainty in the Evidence) (see Corticosteroids)